National wealth, levels of conflict, and gender may determine who gets a jab

At a time when almost half of the world’s population has received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine, and Israel and the nations of North America and Europe have established COVID-19 booster shot programs for their citizens, African leaders are navigating a pandemic in which less than four percent of the African population has been fully vaccinated.

With backing from the World Health Organization (WHO), South Africa’s Afrigen Biologics and Vaccines is working to reverse engineer the Moderna vaccine in an effort to produce doses that are guaranteed to reach Africans within a year. The WHO officials cite the urgent need for coronavirus vaccine access in Africa as the reason the organization is for the first time supporting alternative vaccine production without permission from the developer. According to the Associated Press, the intellectual property protections are unclear in this case, but Moderna says it will not sue the Cape Town-based company for these efforts. Moderna also states that it has plans to build a vaccine production facility in Africa, but there is no date currently associated with the project. In the meantime, several prominent public health experts are supportive of the efforts by developing nations to provide their own vaccine supplies. The former head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S. CDC), Tom Frieden, says the world is “being held hostage” by Moderna and Pfizer because these companies control the vaccine supply chain.

At a September meeting of the U.N. General Assembly, some of these leaders were demanding answers as to why almost six billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in just 10 wealthy nations. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa urged the U.N. to support a proposal to temporarily waive vaccine makers’ intellectual property rights so that low- and middle-income countries may produce their own vaccine supplies.

“It is an indictment on humanity that more than 82% of the world’s vaccine doses have been acquired by wealthy countries, while less than 1% has gone to low-income countries,” President Ramaphosa told the General Assembly. Namibian President Hage Geingob went further, calling the disparity “vaccine apartheid”, comparing it to the system in which South Africa’s white minority controlled the destiny of the Black populations within its own borders as well as those residing in Namibia, then called South West Africa.

Although U.S. President Joseph Biden has offered support for the intellectual property waivers for vaccines, other Western nations have not yet followed suit. Biden has stated that the U.S. should lead the world in making the vaccine available, and the country has thus far donated over 140 million vaccine doses to 93 countries as part of its pledge to provide more than one billion doses to poorer nations. At the same time in an interim statement on COVID-19 booster doses, the WHO has urged the U.S., Germany, the U.K., and Israel to contribute to global vaccination goals instead of offering citizens a third vaccine shot:

“Offering booster doses to a large proportion of a population when many have not yet received even a first dose undermines the principle of national and global equity. Prioritizing booster doses over speed and breadth in the initial dose coverage may also damage the prospects for global mitigation of the pandemic, with severe implications for the health, social and economic well-being of people globally.”

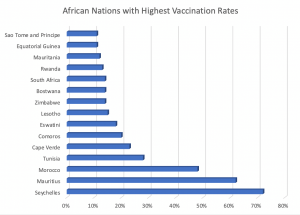

A record 23 million coronavirus vaccines arrived in Africa in September, which was 10 times the number received in June. Yet only 15 Africa nations were able to achieve the WHO target of vaccinating at least 10% of the population in every country by the end of September. Half of the 52 African nations that have received COVID vaccines have been able to fully vaccinate only 2% or less of the population for a total of 60 million Africans who have been fully vaccinated. The WHO reports that COVID cases across the continent dropped by 35% at the end of September, and at the same time, the Delta, Alpha and Beta variants of the virus are taking hold in the majority of African countries.

Since its inception in 2020, 47 African nations have joined COVAX, a consortium of global health organizations, pharmaceutical companies, scientists, and governments that aims to equalize access to COVID-19 diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines. The WHO estimates that six out of seven COVID cases go undetected in Africa. While the alliance has yet to address widespread COVID testing, currently vaccination remains the central focus of COVAX. It aims to provide 600 million vaccine doses to African nations by the end of the year and to vaccinate 60% of the African population by the summer of 2022. In addition to promoting international vaccination solidarity, the COVAX proposal has also inspired collaboration among African nations with Senegal donating 20,000 vaccine doses to its neighbours, the Gambia and Guinea Bissau, in early 2021 and Algeria sharing 250,000 doses of its supply with Tunisia during the summer.

According to the WHO, this type of mutual support is required to end the global suffering caused by the pandemic. “Science has played its part by delivering powerful, life-saving tools faster than for any outbreak in history,” said WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. “But the concentration of those tools in the hands of a few countries and companies has led to a global catastrophe, with the rich protected while the poor remain exposed to a deadly virus. We can still achieve the targets for this year and next, but it will take a level of political commitment, action and cooperation, beyond what we have seen to date.”

Conflict

At the other end of the continuum of intra-African cooperation is the impact of conflict on the continent. Even before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, warfare within and among African nations was contributing to low vaccination rates. A 2019 vaccination study by the U.S. National Institutes of Health surveyed 16 war-torn nations, 11 of which were in Africa. The findings showed that although these nations represented 12% of the global population, they were home to 67% of the polio cases and 39% of the measles cases with soaring rates for other preventable infections like diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus. The study noted that world health investments tended to emphasize vaccine provision through existing government relationships with little experience in meeting the needs of those most impacted by the conflicts or providing vaccines through civil partnerships.

Today there are at least 15 African nations at war, and Ethiopia provides a daunting example of the many ways that conflict serves as a barrier to COVID-19 vaccination. In addition to multiple regional conflicts, the focus of the East African nation is on the Tigray War, which has crippled the economy, displaced hundreds of thousands who are fleeing the bloodshed and created famine conditions for millions who require immediate food aid.

Ethiopia received its first 2.2 million AstraZeneca vaccine doses in August through COVAX, and this was supplemented by almost one million additional doses donated by China and the U.S. Yet the Gavi vaccination alliance notes that the vaccines are primarily administered in urban centres, while almost 80% of the population lives in rural areas. Ethiopia is focusing its human and financial resources on the war, leaving little money or intellectual capital to fight COVID. Although Ethiopia has allocated the U.S. $328 million for COVID-19 vaccines, this represents only a quarter of what is needed to inoculate its citizens. Ethiopia is also accused of blocking food assistance, telecommunications, electricity, and healthcare to Tigray, leaving little opportunity for the regional government to prioritize the fight against coronavirus.

Gender matters

Although there is no source for global data about how many women are being vaccinated, public health experts have noted that women in Africa’s poorest nations remain largely unvaccinated. In addition to limited access to primary health care, misinformation among women seems to be spreading faster than COVID testing or vaccinations.

Confronted with the reality that only 18% of pregnant women in the U.S. have been vaccinated, the U.S. CDC is trying to persuade them that studies show that their unborn children will not be negatively impacted nor will these women have difficulty conceiving in the future if they receive a vaccine. Meanwhile, the African CDC is encountering resistance from African women who are hearing that vaccines cause blood clots, miscarriages, and infertility. Some of this discussion may arise from early reports that the AstraZeneca vaccine can cause life-threatening blood clots.

As public health workers share pro-vaccine T-shirts and talk to women about the fact that blood clots occur in only about four out of every one million people who receive the AstraZeneca vaccine, they hear a recurring suspicion expressed about the prevalence of the AstraZeneca vaccine in African countries: Africans are being given vaccines that no one else wants. A recent Associated Press report from the Gambia noted that a belief among many women that the vaccine will kill them by stopping their blood flow resulted in part because of a poor translation of the phrase “blood clot” into local languages.

Beyond this, assurances that vaccines cause only occasional, mild side effects is not comforting to women who cannot afford to miss even one day of work. Women are not alone in this fear. The pandemic has had a widespread negative impact on African economies, triggering substantial gross domestic product reduction in 2020. While Southern Africa experienced the sharpest decline at negative seven percent, most of Africa’s key economic drivers have been hit by the pandemic. The drop in global oil prices may have brought a sigh of relief to many Western drivers, but in Nigeria, the continent’s leading oil-exporting country, this decline led to a recession by late 2020. Across Africa, the pandemic-driven collapse of the tourism sector led to the loss of over 12 million jobs, many held by unskilled female workers who are now struggling to make ends meet. The number of people living in extreme poverty in Africa increased by about 30 million in 2020, according to the Brookings Institution.

***

The WHO says it remains committed to ensuring that 70% of the world is vaccinated by June 2022. Rather than a decentralized approach that relies on each nation making vaccination decisions, the organization says there should be a universal, three-step approach to vaccinating against coronavirus: first vaccinate older adults, health professionals, and high-risk groups, then all other adults, and finally adolescents. To reach this worldwide goal, at least 11 billion vaccine doses must be available, and the WHO says a sufficient supply is being produced to achieve these global targets. What remains to be seen is whether there is an international will to ensure that these vaccines reach all nations.

From the helm of the U.N. at the September meeting of the General Assembly, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres urged global cooperation. “Without a coordinated, equitable approach, a reduction of cases in any one country will not be sustained over time,” he said. “For everyone’s sake, we must urgently bring all countries to a high level of vaccination coverage,”

This sentiment was echoed by African leaders, including the president of Chad, Idriss Déby Itno, who told the U.N. General Assembly that national wealth alone will not protect against a global pandemic. “The virus doesn’t know continents, borders, even fewer nationalities or social statuses,” he said. “The countries and regions that aren’t vaccinated will become a source of propagating and developing new variants of the virus. In this regard, we welcome the repeated appeals of the United Nations secretary-general and the director-general of the WHO in favour of access to the vaccine for all. The salvation of humanity depends on it.”