The euphoria concerning the potential of new technologies to transform society and increase democracy is based on a flawed instrumentalist assumption that technologies by themselves have transformative power, but ICT access and online political deliberation or activism in sub-Saharan Africa cannot automatically be interpreted as a sign of deepening democracy and accountability

When a paper on new media and social protests in South Africa was presented at a roundtable seminar at the University of Witwatersrand in 2011, the familiar, almost inevitable view was raised that Africans’ use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) is still low compared to other regions due to the “digital divide”. In response, one panellist stood up and said: “Yes, it is true that the digital divide exists in Africa – but we also know that millions of people on the continent are connected to the internet and social media platforms. Our attention should then be drawn to consider how these millions are using new technologies. We cannot run away from the real presence of ICTs in sub-Saharan Africa.”

Indeed, Africa is connected. Recent statistics show that 26 percent of the population used the internet by the end of 2014. As for mobile phones, “[a] report by Swedish telecommunications company Ericsson said that mobile subscriptions in sub-Saharan Africa were set to surpass 635 million by the end of 2014 – a figure ‘predicted to rise to around 930 million by the end of 2019.’”

There is no doubt that digital technologies have contributed to a dramatic shift that has empowered individuals and non-state actors on an unprecedented scale. Characteristically networkable, dense, compressible and interactive, ICTs provide (in theory) greater opportunities for political participation and engagement than do the traditional mass media. We have seen new media technologies open up civic engagement across the globe, albeit with tensions and contradictions.

In Africa, political participation and civic engagement have been restricted by both colonial and postcolonial political and socio-economic realities. The “public sphere” and media systems under colonialism were restrictive and exclusionary, leading black people to create various forms of subaltern counter-public spheres. The postcolonial state did not fundamentally alter the situation and the continent witnessed attempts by successive post-independence governments to limit access to information. Despite the opening up of media space during sub-Saharan Africa’s “third wave” of democratisation in the 1990s and the toppling of many one party states, restrictions have continued, as freedom-of-expression organisations such as the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) and the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) continue to report. Traditional media’s democratic potential has been curtailed by different shades of authoritarianism and economic imperatives. In many cases, colonial laws that had banned or inhibited forms of expression were maintained, and sometimes enhanced.

Many people hail the proliferation of ICTs as ushering in a “fourth wave” of democratisation on the continent. The new media technologies promise to include a greater number of people in the mediated public sphere. Citizens can bypass both state or market media restrictions, as seen in the Arab Spring in 2011 and food riots in Mozambique in 2010. However, questions still remain about the extent to which ICTs are facilitating political participation and how much this is leading to greater democratisation and accountability on the continent.

The Contradictions of ICTs in (Post-) Repressive Contexts

There is no question of the link between democracy and access to information. No genuine democracy may exist without vibrant media and an informed citizenry, and yet the media–democracy nexus in sub-Saharan Africa has been fraught with challenges. New media technologies appear to resuscitate hope for social and political change in Africa and, indeed, ICTs have been at the centre of the democratic project in many countries. In repressive and post-repressive countries such as Ethiopia, Zimbabwe and Sudan, they have sometimes successfully enlarged the democratic project. At other times, they have been obstructed. In Zimbabwe, for example, ICTs allowed activists and ordinary citizens to sidestep the restrictive media laws passed by the ZanuPF government between 2000 and 2008. The monopoly on information that the governing party had held since independence in 1980 was broken as people began to access independent news and discuss politics on social media platforms. ICTs enabled the public to subvert the dominant discourses peddled by the state-owned media.

A key issue is the role of mobile phones in general elections in Africa. In Zimbabwe, election results have long been widely disputed, with allegations of rigging, vote-buying, coercion and other irregularities. In 2008, citizens used text messages to monitor the elections, and any instances of irregularities were shared on mobile phones. Similarly, in Sudan’s 2010 elections, civil society organisations used the Ushahidi platform to support the independent monitoring and reporting of the country’s first multi-party elections in 24 years. With web and SMS reporting, the Sudan Vote Monitor (www. sudanvotemonitor.com) attracted wide interest from citizens and other organisations. Across the continent, elections are no longer the preserve of political parties, the mainstream media, electoral commissions and observer missions. Citizens are playing a more prominent role in monitoring and safeguarding their votes.

The Ethiopian regime has recognised the power of ICTs to empower citizens and give them a voice. As a result, it has repeatedly censored internet content, closed websites and intercepted SMS messages using highly sophisticated tools. Bloggers and online journalists have been arrested under the country’s harsh laws. As the digital infrastructure is mostly state-owned, government is in a position of complete control.

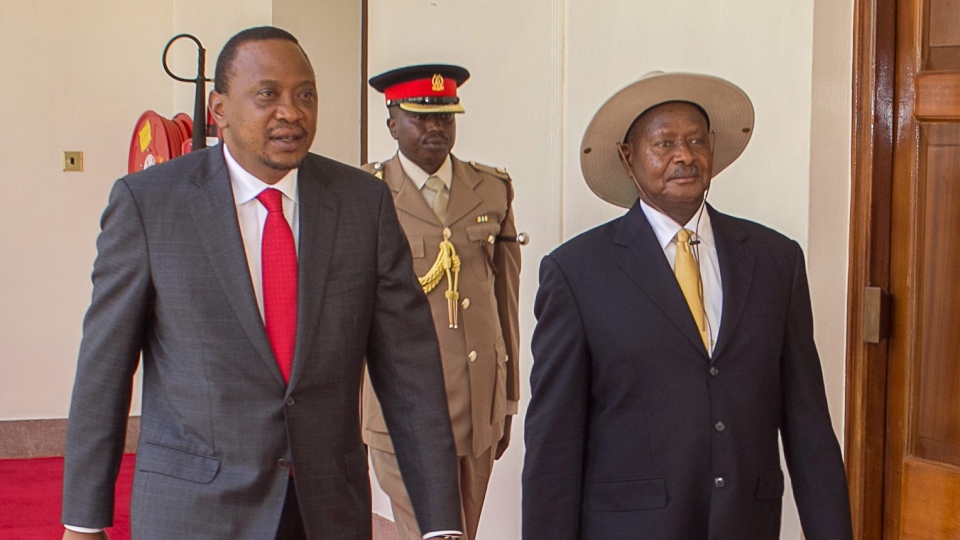

There has also been an increase in states using laws against defamation or subversion to prosecute online expression, and not only against journalists. Citizens have been arrested for comments that are said to offend or to pose threats to national security. The first such incident happened in Zimbabwe in 2011, when a Facebook user posted a message to the page of then-Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai that referred to the Arab Spring and the shockwaves it was sending to dictators. In Kenya, a Facebook user was arrested in 2012 for making a defamatory comment towards an assistant minister in the government. In 2015, a 25-year-old Kenyan man was jailed for insulting President Uhuru Kenyatta in a post on a social media site.

While many governments are clamping down on ICTs, they are also using them for their political campaigns. In the 2011 Zambian elections, political parties for the first time communicated their messages via websites, social media pages and bulk SMS messages. The same happened in elections in Uganda in 2011, Kenya in 2013, South Africa in 2014 and Nigeria in 2015.

From the discussion above, we see that digital technologies offer both opportunities and risks. On the one hand, they offer democratising, emancipatory and mobilising potential. On the other, they open the way for repression and surveillance.

ICT, Social Mobilisation and NGO Movement Building

“We use Facebook to schedule our protests, Twitter to coordinate and YouTube to tell the world.” (Egyptian activist)

Since the 2010/11 Arab revolutions, the role of new media technologies in allowing ordinary people to effectively organise themselves for political change has been a hot topic. Although writers such as Malcolm Gladwell and Evgeny Morozov warn against techno-euphoria, stating that ICTs reinforce existing political structures rather than transforming them, there is no doubt ICTs facilitated – and accelerated – the revolutions in both Tunisia and Egypt. Since then, we have seen innovative use of these technologies in mobilisation and the adoption of decentralised, non-hierarchical organisational forms in social movements and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). For instance, in Malawi, digital technologies played a central role in prior to, during, and following the national demonstrations against poor governance in July 2011. People gathered, posted and updated information via social networks on a scale not seen before.

At the same time, social mobilisation has been affected by state disconnections and restrictions. Uganda shut down Facebook and Twitter for 24 hours during the Walk to Work protest in April 2011. In the 2010 Mozambican food riots, the government ordered cellphone operator Vodacom Mozambique to shut down its SMS services. Similarly, the Central African Republic shut down SMS services of all four mobile phone companies for eight weeks in the midst of political demonstrations against the transitional government that came to power in January 2014. In April 2015, during waves of protests opposing Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza’s bid for a third term, phone lines of private radio stations were cut.

Digital Inequality and the Need to Strengthen “Old Media” Ecologies

As ICTs have spread across the continent, those who have little or no access are becoming increasingly marginalised. Although mobile phone penetration is nearing the 100-percent mark in many countries, there is still a divide between those with access to smartphones and those without. As more affluent people get access to faster broadband, those who do not, especially in the rural areas, become ever more distanced from the kind of political participation the new technologies allow. The differentiated uses and knowledge of ICTs, whether through lack of access, lack of interest or lack of computer literacy, is creating “digital inequality”. Those with digital capital participate more fully in digitally mediated spaces and enjoy many advantages over their digitally disadvantaged counterparts.

While focusing on the positive changes brought about by new technologies, it is also important to keep in mind that these new forms of communicating, interacting and networking do not replace traditional modes of political and civic engagement. A “communicative ecology” approach explores the modes of communication and media that are available to communities in their locales. Communicative ecology theorists distinguish different “layers”, intricately entwined and mutually constitutive, which can provide opportunities for empowerment: discursive (themes or content of both mediated and unmediated communication), technological (ICTs, TV, radio), and social (community meetings, informal networks, institutions). Our accounts of the relationship between citizens, media and political participation should include traditional (or old), new, and alternative media in their entirety, including such forms as theatre, music, art, spoken-word poetry, etc. A case in point is the Burkina Faso revolution in October 2014 that ended the 27-year presidency of Blaise Compaoré. Organic, people-driven and with little reliance on digital technologies, the revolution managed to gather thousands of people at the Place de la Nation in the capital. Their tactics also need to be documented.

Enclosure of the Digital Commons?

The increasing demand for smartphones in Africa has run in tandem with growing state interest in mobile telephony. Through SIM registration – the most pervasive form of control across the continent – service providers are obliged to collect their customers’ personal data (name, current address, profession etc.) for the state. Since no registration means no access to service, people comply with procedures whose consequences they might not be aware of, although these regulations have a range of implications for inclusion, surveillance and development.

Another area of concern is threats to the privacy and security of users, whether from state surveillance or third-party access. For instance, applications such as Google, which come already installed on most Android devices, have the ability to read and analyse usage and adjust themselves to the user’s preferences. Such capabilities can be beneficial to a user, for their convenience and computing genius. However, they can also be compromising in the hands of a state bent on limiting political participation by creating a culture of censorship and digital insecurity.

In the absence of digital literacy, and with the insistence on a single narrative with regards to mobile telephony in Africa (“mobile is accelerating development”), most governments have created legal frameworks that allow them to build massive surveillance capabilities to monitor and intercept the private communications. In most countries, the vulnerability of citizens to state power has become a permanent feature. ICTs have increased this vulnerability.

The African Union’s Draft Convention on the Confidence and Security in Cyberspace notes that: “Africa is faced with security gap [sic] which, as a result of poor mastery of security risks, increases the technological dependence of individuals, organizations and States on computer systems and networks that tend to control their information technologies needs and security facilities. African States are in dire need of innovative criminal policy strategies that embody States, societal and technical responses to create a credible legal climate for cyber security.”

Although states have a legitimate responsibility for ensuring digital security for its people, the language of the African Union paints a picture that prioritises restriction above freedom, of digital enclosures rather than an enlargement of scope and possibility. The near silence from African civil society regarding state surveillance could indicate the extent to which African governments have succeeded, quite secretively, to pursue policies and legislation that inspire digital insecurity. Hence, there remains an urgent need for sincere inclusive dialogue that can give as much weight to citizens’ rights to online privacy, security and expression as is given to their rights offline. Surveillance of online platforms contributes to an atmosphere of self-censorship.

Conclusion

This paper has taken a mixed view of the role of ICTs for broadening democracy. There is no doubt that they have radically changed the media and communications landscape in Africa, in the process opening up new spaces for communication, political deliberation and free expression. For civil society actors and social movements especially, digital media and online social networking applications have changed the way in which dissent is organised.

However, ICT access and online political deliberation or activism in sub-Saharan Africa cannot automatically be interpreted as a sign of deepening democracy and accountability. The euphoria concerning the potential of new technologies to transform society and increase democracy is based on a flawed instrumentalist assumption that technologies by themselves have transformative power. There also seems to be no direct link between the increase in digital users and improvements in democracy. For example, Nigeria and Kenya stand out for their increase in ICT users, but we also see deteriorating human rights and governance issues in these countries.

Political participation through digital media also seems to be threatened by the steady rise of various surveillance tactics that are being introduced by governments around the continent. Repression in the offline world seems to be encroaching on digital spaces.

As the dominant, but restrictive, macrolevel developmental readings of ICT usage in Africa are slowly giving way to studies that focus on African ICT users and their practices, there is still need for more nuanced studies of the actual relationship between ICTs, democracy and social change. Apart from the few examples in North Africa, there is little documentation from other parts of Africa of how ordinary activists and social movements use the tools of digital technology to enhance their struggles.