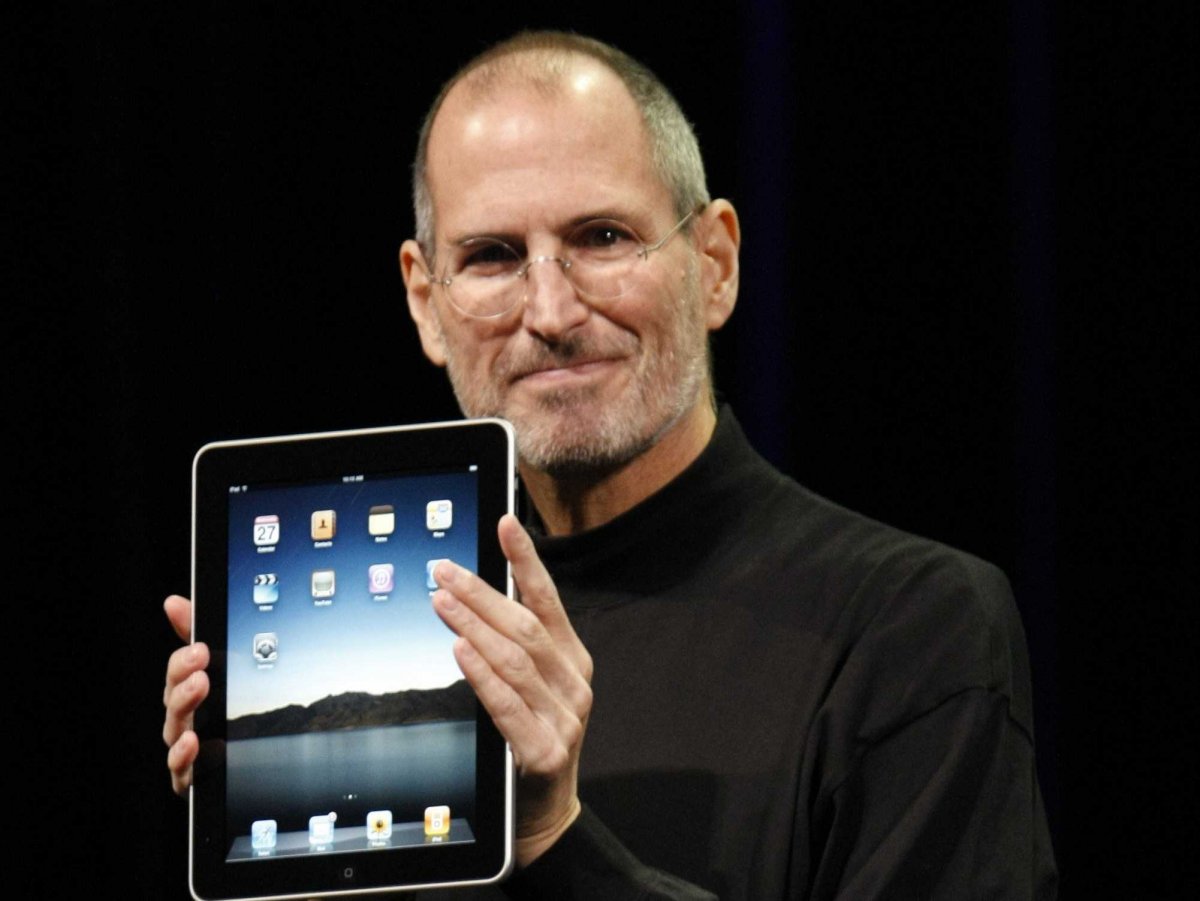

Malawi’s President Joyce Banda is coming under fire over her government’s handling of the scandal [EPA]

Blantyre, Malawi – With more than $250m siphoned off from government coffers, citizens here want officials to speed up the prosecutorial process in what has become the country’s biggest financial scandal.

The corruption affair – known as “Cashgate” – is believed to be rooted among the highest echelons of Malawi’s government, and has led to some $150m being withheld by donors under the Common Approach to Budgetary Support (CABS) scheme.

This has come as a significant blow to the country, as 40 percent of its national budget comes from donor aid.

Sara Sanyahumbi, a former deputy chairperson for CABS, told reporters that the donation freeze is caused by a lack of confidence in the government’s financial management.

The funds will only be released once donors are satisfied with the outcome of government investigations into the scandal, said Sanyahumbi.

“We have seen that the origin of the crisis [was] not a couple of individuals involved in mischief, but [in] systematic issues of public finance management – and it is not that easy to address this in the timeframe that we have,” said CABS chair Alexander Baum.

“As a partner who put European money into the budget of another country, we must have enough trust that the systematic issues are really being sufficiently resolved, and this takes time,” Baum, also the European Union’s representative in Malawi, told local radio.

Loopholes

Investigators have blamed loopholes in a government payment system which enabled cash to be illicitly claimed. Police reportedly found huge sums of money stashed in car boots and homes belonging to the suspects.

The payment system was frozen for five months, during which bureaucrats worked to tighten the regulations and shut off any opportunities for dodgy dealings.

The Cashgate scandal came to light in September, just a few days after an assassination attempt on then Budget Director Paul Mphwiyo, who is believed to have been targeted because of his bid to end financial corruption within Malawi’s politics.

More than 60 people – including civil servants, politicians and business owners – were arrested and charged in connection with the scandal, and 33 private bank accounts were frozen. Properties suspected to have been acquired with stolen money have also been seized.

However, public outrage is continuing to mount over the pace at which the government is handling the case.

Of the 68 suspects, only two have gone to trial – and those hearings only kicked off last week. The trial of business owners Caroline Savala and Angela Katengeza, who were accused of money laundering, was adjourned to give Savala’s new lawyer time to study the case’s legal material. Her previous lawyer, former Justice Minister Raphael Kasambara, has been arrested and is facing his own corruption charges.

On February 5, the start of the trial of Kasambara and businessman Pika Mandondo was also delayed.

Election fears

The adjournments have raised fears among Malawians that the trials will drag beyond elections expected on May 20.

“I am not happy with the progress of the cases,” said Rachel Ziwa, a resident of Blantyre’s Ndirande Township. “Just imagine, five months after the arrests, only trials of two suspects have so far started. Worse still, both trials were adjourned to undisclosed dates. This is outrageous, we want to know who was masterminding the stealing of our money from the government before elections – so that we should make informed decisions on who to vote for.”

John Chikalipo, from Bangwe Township, said he would not vote during the forthcoming elections unless the case was resolved and those responsible were jailed.

“I don’t want to make the mistake of voting for someone who deliberately messed up the economy,” he said.

Four political parties are set to dominate the polls. The governing People’s Party, led by President Joyce Banda, will face off against the opposition Democratic Progressive Party, led by Peter Mutharika, the Malawi Congress Party, led by Lazarus Chakwera and the United Democratic Front – whose presidential candidate is Atupele Muluzi.

Hunting ‘the big fish’

While all four will compete in the election, the People’s Party and the Democratic Progressive Party are finding themselves in the spotlight, with members of both parties popularly accused of pilfering public funds. Investigations revealed the Cashgate thefts had been going on since at least 2006, at which time the Democratic Progressives were in power, leading this southern African nation from 2004 until the death of its leader Bingu wa Mutharika in 2012. Both parties vehemently deny all accusations.

Human rights campaigner Billy Banda (no relation to President Banda) also expressed his reservations over the “narrow way” the government’s prosecution team is handling the Cashgate crisis.

“The most honest answer I can give you is that there is no progress at all,” he told Al Jazeera. “Instead of putting a total commitment to ensure that ordinary citizens are given back what is due to them, they are starting cases involving people who are not directly involved in Cashgate.”

Banda, the executive director of the rights NGO, Malawi Watch, said it would be more prudent for the judiciary to begin with high-profiled figures. “Not the small fish that may not be able to point a finger at the president – who is also suspected to have played a role in the scandal.”

President Banda’s swift announcement of reforms, including the establishment of a new police unit focused solely on public finance and new anti-corruption regulations, has been seen as a positive step, but many here believe her political future remains under threat.

In a court appearance in November, former Justice Minister Kasambara said he would need President Banda to appear as one of five witnesses.

President Banda has also been linked to the scandal by a senior figure in the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, who allegedly was part and parcel of Cashgate – an allegation trashed by Banda’s political allies.

Checking cheques

Meanwhile, local entrepreneurs say the scandal has greatly affected business transactions, as banks are treating government cheques with suspicion.

Mike Mlombwa is the president of the Indigenous Business Association of Malawi. He told Al Jazeera of new delays to conducting business: “If you have deposited a government cheque, it is taking over seven days to clear it – unlike during the time before Cashgate, when you would cash it within a day or two.”

He appealed to officials to speed up the trials, saying donor confidence has to be restored – or the already fragile economy would be further damaged.

CABS Chairperson Baum said that, even with a commitment from Malawi’s government to show it was getting to the root of the scandal, it will still take a while before donors release the money being held.

“We cannot automatically disburse funds into a public finance management system which is dysfunctional,” said Baum. “We have a responsibility towards our own taxpayers and we have our own fiscal crisis in most European countries – as you can see on the world news every day.”

This has dashed hopes that donors would automatically take a leaf from the International Monetary Fund, which is expected to release aid money soon after an initial report is presented on February 14. The report’s executive summary, released in January, was enough to convince IMF officials to distribute some $20m it had withheld under the Extended Credit Facility.

Marking a national Anti-Corruption Day on Wednesday, in the capital Lilongwe, President Banda said that despite facing challenges in the fight against corruption, she would press ahead and continue the steps she has already taken, even if it means sacrificing her political career.

She asked for patience, saying investigations were being handled by competent authorities.

“I will do everything to go deep down into the root of Cashgate scandal – even if it means losing elections,” she said.

“I would like to promise that everyone involved will be charged and prosecuted accordingly – even if it is my son or my husband.”