Imagine living in a world where you are completely unaware of your surroundings. It’s like being stranded on an island without a ship to save you. You get irritated, bored, and lost. But at that point, journalism steps in to inform, amuse, and educate human society.

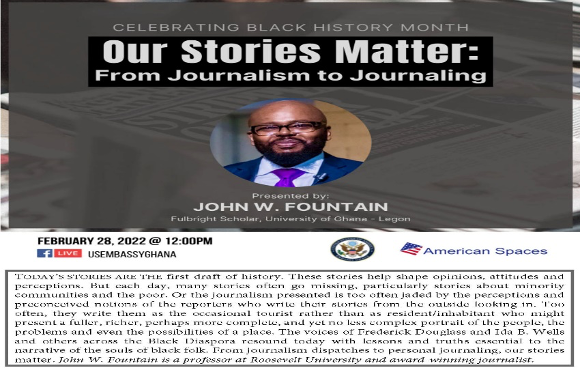

John W. Fountain, a former Journalist with the Washington Post, has won numerous honours.

When he’s not penning prestigious articles or one of his many books, he serves as a preacher at a nearby church.

When he’s not penning prestigious articles or one of his many books, he serves as a preacher at a nearby church.

When he arrived in Ghana as a Fulbright Scholar, Africa Leadership Magazine had the opportunity to grill him on his journalism journey. He worked to impart his knowledge to a new generation of African Journalists.

Can you tell us briefly about your background growing up?

I grew up in Chicago in the 1960s and 70s in a place called “K-Town.” My neighbourhood was located on the city’s West Side and among the nation’s poorest. Its proper name is “North Lawndale.” The Chicago Tribune 1985 launched a series titled, “The American Millstone,” which focused on life and poverty in my neighbourhood. The Tribune’s editors titled it the “Millstone” series because they said we were the millstone draped around America’s neck, that we did not have middle-class values or aspirations, were a drain on society’s resources, and made the case for social triage for a people deemed the “permanent underclass” who would never amount to anything. A few years later, I walked into the Tribune newsroom, a son of North Lawndale, a proud product of Chicago’s West Side, and proof that their series was as wrong as it was racist.

Why did you choose journalism out of so many careers?

I have always loved writing, ever since I was a little boy growing up on the West Side of Chicago. I loved writing poetry on the days when it was too cold or rainy to play outside. In elementary school, in creative writing, I would write fictional stories about talking leaves and all sorts of things. We read our stories aloud in our writing circle and occasionally I would look up and see my classmates laughing and engrossed in the stories I read. It was an amazing high and introduced me early on to the power of storytelling.

I have always loved writing, ever since I was a little boy growing up on the West Side of Chicago. I loved writing poetry on the days when it was too cold or rainy to play outside. In elementary school, in creative writing, I would write fictional stories about talking leaves and all sorts of things. We read our stories aloud in our writing circle and occasionally I would look up and see my classmates laughing and engrossed in the stories I read. It was an amazing high and introduced me early on to the power of storytelling.

Still, I grew up always dreaming of someday becoming an attorney. It wasn’t until my freshman year at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that I began to think otherwise. I had written an essay for a freshman writing class titled, “I Am A Shadow.” I had read Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” in high school and was intrigued by the concept of Black men being invisible to many in society. It also struck me strange in the sense that as a young Black man I never felt invisible because white people often reacted adversely to me when I was in their presence: in elevators, on the street, and in the classroom. I felt not invisible but more like a shadow. I explored that concept in my essay. My teacher loved it and even copied it for other freshmen writing classes to read and analyze. We met in her office one day and she said, “Have you ever thought about becoming a journalist?” And just like that, the seed was planted.

I chose journalism ultimately because of its power to make a difference, to shine the light on hidden corners of the world, to give voice to the voiceless, and to make the invisible visible.

Can you tell us your experiences in the journalism field which you felt motivated you to not give up?

At a very discouraging time early on in my journalism career, I telephoned one of my Black male journalism friends to talk about the difficulties and the racism I was experiencing in the newsroom. The first four words out of his mouth were: “Never internalize their disrespect.” I typed those words, printed them out in a sign in big bold letters, and hung them above my desk. I have carried a sign with those words throughout my career in journalism and also academia. At another time of discouragement, I asked another Black male colleague who was a Pulitzer Prize winner, “Man, how do you deal with this mess?” He responded, “You can’t argue with excellence. Be excellent.” That is always my endeavour.

How real is racism in the journalism field especially with you practising in a foreign country?

Racism is as real in mainstream American journalism as the sun that rises each day. It is glaring and shows itself in prime time daily in national and local news broadcasts, where the faces of people of colour are often missing as major news anchors, national and foreign correspondents, and virtually nonexistent in the behind-the-scenes positions of power that dictate news coverage. The effect is a new product that does not reflect the society in its totality, that misses whole swaths of culture and people and stories that remain invisible to the mainstream news status quo. That has to change. Democracy depends on it.

Racism is as real in mainstream American journalism as the sun that rises each day. It is glaring and shows itself in prime time daily in national and local news broadcasts, where the faces of people of colour are often missing as major news anchors, national and foreign correspondents, and virtually nonexistent in the behind-the-scenes positions of power that dictate news coverage. The effect is a new product that does not reflect the society in its totality, that misses whole swaths of culture and people and stories that remain invisible to the mainstream news status quo. That has to change. Democracy depends on it.

Can you tell us some similarities and differences in journalism today you might have observed from experience?

A glaring difference between journalism today and journalism “yesterday” is the impact of technology, which has made the delivery of news instant, created a 24-hour news cycle and broadened the potential impact or voice of even small news organizations or independent voices. What’s also different is that there is a flood of information in the universe, which inundates the Internet and airwaves. Among the impacts is that it muddies the water between what is “journalism” and what isn’t. And yet, the fundamentals and principles of journalism held true by its true practitioners can help journalism shine just as brightly, even in a deepening sea of misinformation and information oversaturation.

A glaring difference between journalism today and journalism “yesterday” is the impact of technology, which has made the delivery of news instant, created a 24-hour news cycle and broadened the potential impact or voice of even small news organizations or independent voices. What’s also different is that there is a flood of information in the universe, which inundates the Internet and airwaves. Among the impacts is that it muddies the water between what is “journalism” and what isn’t. And yet, the fundamentals and principles of journalism held true by its true practitioners can help journalism shine just as brightly, even in a deepening sea of misinformation and information oversaturation.

What is your opinion about the influx of media schools in Ghana? Does it have any effect on the quality of journalism we see today?

I’m not knowledgeable about any “influx” of media schools in Ghana. My opinion about journalism schools and education in general, however, is that any school that engages in the education of young journalists—teaching them the principles and the fundamental skills of news reporting and gathering, and ethics, which will stand the test of time—has to be a good thing. Especially if they are teaching not journalism theory but journalism skills. The actual practice, moves beyond the ivory tower and the newsroom into the street, into communities to capture the faces, voices and issues and extraordinary stories of everyday people.

Many say journalism does not pay, what do you think about this assertion?

It depends on what you mean by “pay.” Being a journalist, for me, has never been about money. It is about making a difference, about being a voice for the voiceless. It is the opportunity to make a difference in the lives of others through the power of journalistic storytelling. Of course, I needed to be able to pay my bills too. And every journalist should have the ability to do so—to live by their craft. It is imperative that journalists make a decent living wage. Our contribution to democracy is indeed priceless. Journalism does indeed pay, maybe not necessarily in impressive monetary sums across the board, but also in ways that are rewarding, lasting and priceless.

What do you have to tell upcoming young journalists about the journalism world?

Journalism needs you. Be strong, vigilant and faithful. Hone your craft and never give up. Remember: Journalism isn’t about you, it’s about the story, always the story. And finally, remember: “Never Internalize Their Disrespect” and “You Can’t Argue with Excellence.” Onward and Upward.

Journalism needs you. Be strong, vigilant and faithful. Hone your craft and never give up. Remember: Journalism isn’t about you, it’s about the story, always the story. And finally, remember: “Never Internalize Their Disrespect” and “You Can’t Argue with Excellence.” Onward and Upward.