Johannesburg — Southern Africa’s biggest metropolis has big plans to become one of the continent’s greenest cities.

With Addis Ababa, Cairo and Lagos, Johannesburg has joined the network of megacities across the world – known as the “C40 Climate Leadership Group” – which aims to play a leading role in moving quickly to combat climate change.

If successful in its efforts, Johannesburg could set the pace for efforts experts say are essential to making and keep cities livable. The challenges are enormous.

By the time today’s babies are in their mid-30s, the percentage of the world population living in cities is expected to rise from half to three-quarters – 6.2 billion people! African cities, by most accounts, are growing the fastest. With pressures on essential services such as water, sanitation and health facilities – plus the need for housing and jobs – communities and policy makers must scramble to catch up, let alone to get ahead of the curve.

Climate change is one of the ‘shocks’ that planners will have to accommodate. From urban coastlines that are already flooding due to sea level rises to the urgency of reducing greenhouse emissions, cities are searching for solutions. Land-locked Johannesburg, built to profit from rich veins of gold far underground, is now looking to profit from innovative appreaches to a changing climate.

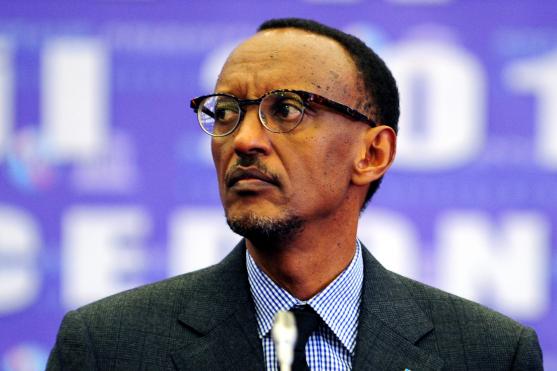

In a recent speech at a C40 group meeting, Johannesburg Mayor Parks Tau waxed eloquent about his city’s plans and action.

A South African-German collaborative project has begun an inventory of Johannesburg’s greenhouse gas emissions. The project aims to introduce innovative energy supplies for Johannesburg and two other municipalities in the surrounding Gauteng province which between them comprise 10 million inhabitants.

But many of the city’s environmental initiatives are at an early stage of implementation. A run-down on how Johannesburg is doing:

One person’s waste is another’s energy

About 470,000 households are being encouraged to separate out their waste so that it can be recycled where appropriate at seven different sites in the city.

Recyclables such as paper, tin, plastic and glass are collected in clear plastic bags from households and go to local garden waste sites where it is planned that about 25 co-operatives will sort and sell the materials to recycling companies.

According to Musa Jack, executive director of waste minimization at Pikitup, the city-owned waste management entity, the first co-operative was set up at the Linbro Park landfill in north-eastern Johannesburg.

At Linbro Park, there are areas demarcated for sorting, with containers for recyclables and garden waste. A roof to protect to workers is planned.

In the south of the city, Robinson Deep landfill city boasts a fully-fledged materials recycling facility. Most of the members of the co-operatives are women, and the pilot project already handles about 15,000 tons of waste a year. Less waste means less methane – a potent greenhouse gas – and less pressure on new land for dumps.

Tenkiso Phidza, a member of one of the four co-operatives at Linbro landfill, is responsible for logistics. For example, Mphekwana tried to take some waste to a scrapyard by taxi and was told she was not welcome on board.

“Pikitup supplies a truck to help us collect the recyclables in the clear bags but we have to supply the labour to load the trucks and sort the waste. This means we have to pay wages of R100 a day to four men. Thus alone can come to R8000 a month. Making recycling viable is a real concern,” says Phidza.

“At present four of our members want to leave because they are earning nothing,” she says.

“They don’t understand that we are a small business and that sometimes a start-up has to work for nothing. At the same time, poor people still have expenses. If four women leave there will only be five pairs of hands; one woman refolds the clear bags which means only four hands for sorting waste. We would love to get funding to buy a baler. This would make us more efficient. (Waste buyers) Collect-a-Can and Nampak at least come to us to collect waste. Otherwise, we have to take waste to scrapyards or buy-back centres and transport costs money.”

“One month we made R13 000,”says Phidza. “Even in a month as good as this, each woman would get little more than R500 after costs have been deducted. Another month we make R1500 which means we run at a loss.”

Pikitup’s Musa Jack acknowledges the teething problems of the co-operatives. “It’s still early days since this is a two-year project,” says Jack. “We are trying to help the women as much as possible, especially with transport and negotiating prices with buyers of waste. The latter is only successful to a point because buyers are running a business, not a charity. I am not sure why the women are incurring extra costs by hiring labourers however, Most recyclables are light and possibly two or three co-op members could do the lifting themselves. This means all earnings would be for their own pockets.”

Pikitup realises the urgent need to train the women in basic business skills. It initially applied to the City of Johannesburg’s economic development department to educate the women. “There is a long waiting list for skills training so in the mean time we are negotiating with an NGO to provide the women with basic business skills. Pikitup has also negotiated with the Gauteng Economic Propeller (a provincial entity to promote economic development).”

“We are going for an ‘incubator’ approach in which we hope to mentor each co-operative for two years,” says Jack. “We want them to develop sufficient skills and confidence to apply for their own grants and continue to be self-sufficient and generate modest profits.”

Some meetings have been held with the co-operatives but the team needs to get the women to understand realistic goals for their businesses. Setting up a successful business is a process, says Jack, not an overnight phenomenon.

“Waste-to-energy” programmes also planned for the city, although the concept is controversial since it involves burning rubbish at very high temperatures to extract energy. Unless the waste is burned at above 850 degrees celcius, carcinogenic dioxins are produced. Greenpeace says that it is not advisable to produce waste just to burn. “We should be aiming for zero waste. Finding ‘uses’ for waste is a temporary solution.”

Johannesburg is also considering ‘mining’ landfill sites for methane-rich gas, which will be collected at Linbro Park, Robinson Deep and three other waste sites. The gas will be converted into electricity in on-site generators and fed into the city’s power grid.

Some 68 wells have been sunk at Robinson to facilitate the extraction of the gas. Four one-megawatt generators will be installed at Robinson, producing enough power to meet the needs of 5,000 households.

With five landfill sites on line, enough power could be produced to supply 12,500 middle income families.

Keeping the lights on

The city has also installed more than 40,000 smart meters, hot water cylinder control systems and solar heating units.

The 43,000 hot water systems– many of them on the roofs of economical housing projects – produce enough electricity every year to power a small town. Smart meters, which can be remotely controlled by the utility, were put first into factories and commercial buildings, and now about 20,000 residents whose energy use is high have been issued with smart meters too.

The city is also seeking to introduce “time-of-use” tariffs, which would enable it to charge more for electricity used at peak times, such as during the evenings in residential households. These would encourage people to invest in solar water heating and to switch from electricity to gas for cooking.

The city has also announced that it will establish the second of two biogas-to-energy plants, in which methane from fermented sewage will make a sewerage works produce enough energy to run itself.

Driving change

To begin to cut the greenhouse gases generated by the city’s transport system, Johannesburg has launched its first buses powered by a combination of diesel and compressed natural gas.

Lisa Seftel, executive director of transport for Johannesburg, says the bus operator plans to convert 30 more buses to dual fuel use by the end of the year. By February next year it aims to buy 150 new dual-fuel buses.

“Our first two dual fuel buses are emitting 90 percent less carbon than a diesel bus,” says Seftel.

However, since natural gas is a finite resource and produces impacts similar to those caused by mining coal or oil, Johannesburg has greater ambitions than dual-fuel buses – renewable biogas sourced from waste including, grass from parks, waste from crops and the fresh produce market.

Research on options is taking place in the next 18 months with the University of Johannesburg and the South African National Energy Development Institute to refine bio-digesters that non-food agricultural products to produce fuel.

There is also a feasibility study under way on biogas powered taxis, and the city’s new Rea Vaya buses run on low-sulphur diesel, reducing emissions of nitrous oxides and smut by thousands of tons a year.

“Could do better”

According to Greenpeace Africa’s Climate and Energy Campaigner, Ruth Mhlanga, the City has taken some good first steps, but there “must be follow through, consistency and the changes must be more than cosmetic or because they are fashionable. Environmental sustainability must be the focal point for all policy formulation.

“There are rarely bad green initiatives; everything could help, be it litter picking or recycling,” says Mhlanga. “What matters is the scale and consistency. In light of the threat of climate change many programmes amount to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.”

According to Mhlanga, the glaring gap in the initiatives is the Feed in Tariff (FiT). Under this system every owner of a renewable power plant (wind turbine, photovoltaic panel or biogas plant) gets a fixed remuneration for every kWh of electricity produced and fed back into the grid.

The FiT-system pays an attractive rate to encourage investment in renewables.

Targeted regulatory measures invigorate the renewable economy without incurring new debts, says Greenpeace. South Africa has abundant solar resources that could bring down rocketing energy costs and democratise power production.

Mayor Tau says he is determined that his city’s initial steps won’t be the end of Johannesburg’s climate-change adaption story. Having made his initiatives a highly visible feature of a global mayors’ movement, he will be closely watched for results.