Zimbabwe’s multi-currency confusion

For the last five years most people have been using US dollars or South African rand, but pula from Botswana and British pound sterling have also been changing hands.

Now the central bank is also allowing the use of Australian dollars, Chinese yuan, Indian rupees and Japanese yen.

For the moment, customers can open bank accounts in these currencies but the hard cash is not yet in circulation.

“I definitely think there is going to be confusion being caused by so many currencies – for a cashier to be handling so many currencies at the same time,” says Denford Mutashu, general manager of Food World, a nationwide supermarket chain.

Currently most shops in the capital, Harare, mark prices in US dollars. The rand is more commonly used in Bulawayo, closer to the South African border – and cashiers check daily exchange rate for conversions.

Acting central bank governor Charity Dhliwayo says she hopes the move will bring in more cash, as a liquidity crisis has meant some banks have stopped lending, making imports difficult.

But there is concern that with more currencies, transactions could become more tedious, leading to long queues at the till.

“We wait to see how this will shape up. Shoppers want quicker, easier transactions, not to be bogged down negotiating currencies when you are racing against time to get public transport home or to work,” admits Mr Mutashu.

“People don’t have time to waste any more. We will have to find ways to expedite the transactions.”

No coins, just sweets or condoms

The central bank said that over Christmas, when there was a severe shortage of cash, there was also a surge in counterfeit currency.

Given the complexities of the multiple currency system, there are now fears that forgery will be easier with unfamiliar notes.

Some banks in Zimbabwe ran out of money before Christmas

Some banks in Zimbabwe ran out of money before ChristmasHowever, it may mean that small change, which has long been scarce, will become available in shops.

Zimbabwe’s liquidity crisis means shopkeepers and market traders often give change in sweets, airtime for mobile phones and even condoms.

“If it makes our life easier for us, that’s ok. At the moment we don’t have change -if it’s going to make transactions easier, [then it is] better,” said one shopper in his mid-50s, who was buying bread and vegetables in Harare Food World.

Tawanda Huruwa, a small-scale miner, is more cautious about the news that he can open up bank accounts in currencies from four more countries.

“Personally, as a Zimbabwean doing business I am not comfortable with using these currencies. What I want to see is how the banks themselves will respond to the use of these currencies.”

“I am not happy using these currencies,” adds Cuthbert, a 45-year-old taxi driver. “We do not know the currency, even the exchange rates; I do not think it’s necessary to use this currency. Even the banks can lie to us.”

His colleague, Farayi 20, feels the introduction of the yuan heralds yet more influence from China on the economy.

“They are trying to get the whole African market. So it is a way of colonising in some sense. What do we benefit out of this Chinese currency – that’s the big question – because at the moment these guys are not banking here in Zimbabwe but actually they are taking all the money out of Zimbabwe,” he says.

‘Immune from fluctuations’

But a second-hand car businessman says the multi-currency system is an advantage for him.

“We have the option of using many currencies given different clients we deal with,” the Zimbabwean businessman, based in Japan, says.

“We are immune from constant currency fluctuations if we are operating the same currency accounts in Japan and Zimbabwe.”

For economist Christopher Mugaga, the introduction of new currencies is not the solution to Zimbabwe’s economic woes, with its chronic unemployment and shrinking manufacturing sector.

In Harare most people use the US dollar – but small change in particular is in short supply

In Harare most people use the US dollar – but small change in particular is in short supply Some traders worry that counterfeit notes will be a problem

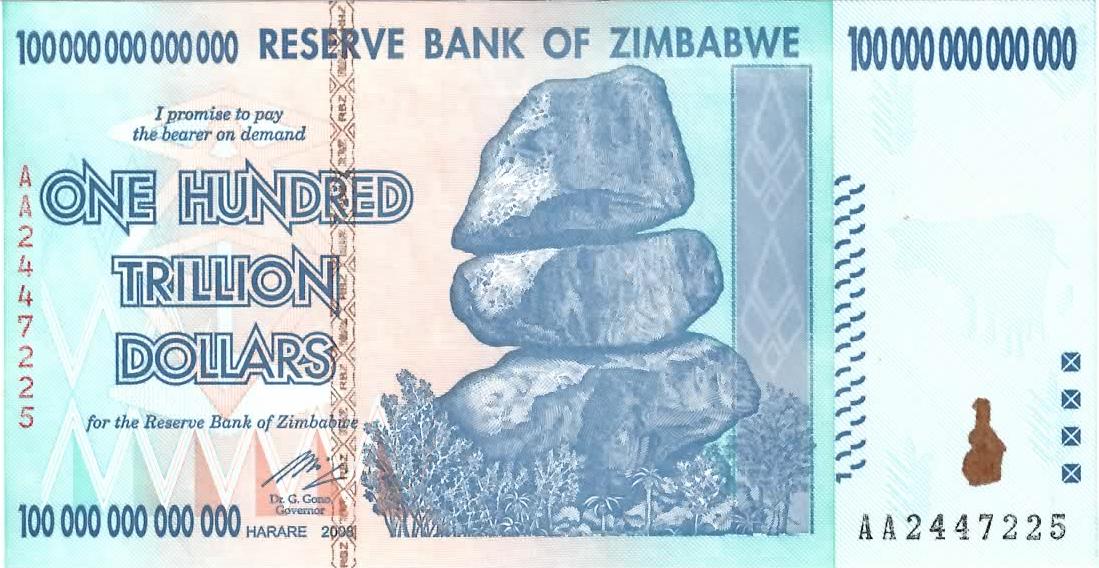

Some traders worry that counterfeit notes will be a problem A 50bn Zimbabwean dollar note issued in 2009 just before the currency was completely abandoned

A 50bn Zimbabwean dollar note issued in 2009 just before the currency was completely abandoned“Bringing on board more currencies will not change the trajectory of any economy,” he said.

“You hear about the corporate bankrupts, companies are closing, shops – our unemployment rate is always on the increase. Banks are almost freezing their loan books simply because the economy is almost in an intensive care unit.

“It’s not all auguring well in terms of trying to attract any investment in the country.”

One elderly shopper in Food World, buying 5kg of the staple food, maize meal, says the severe cash shortages, which meant the festive season was hard to endure, make her nostalgic for the Zimbabwean dollar.

“We want our currency, we want our Zimbabwean money,” she says.

During last year’s election campaign, allies of President Robert Mugabe hinted at this, prompting warnings it could lead to a return of hyper-inflation, which was cured by the introduction of foreign currencies.

However Ms Dhliwayo says the central bank has no such plans, and for Mr Mugaga the prospect is “unimaginable”.

“For the ordinary Zimbabwean it’s going to be quite tough, a difficult year,” he warns.