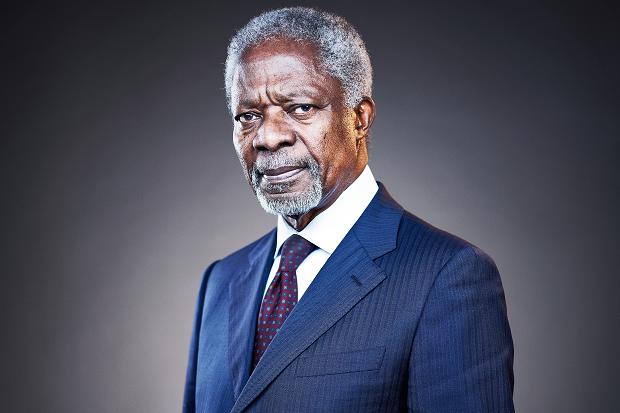

THE WORLD JUSTICE PROJECT Rule of Law index, a new global report that ranks countries’ adherence to the rule of law, puts Botswana in the top spot for Africa. The country’s chief justice, Maruping Dibotelo (pictured at left, with President Ian Khama), was probably not surprised: the diamond-rich southern state has been regarded for decades as among the best-run on the continent. Botswana also placed near the top in the latest Index of African Governance, published annually by Mo Ibrahim, a Sudanese-British telecoms magnate. That guide uses a broader set of criteria going beyond matters of law. While Botswana did not clinch the top spot in Mr Ibrahim’s survey, last published in 2014, it was beaten only by the tiny island states of Mauritius and Cape Verde. On the mainland, Botswana was first. Indeed, on a global scale, the World Justice Project (WJP) report puts Botswana 31st out of the 102 countries measured, one spot behind Italy and two ahead of Greece.

The worst African performer in the WJP report, issued this month, was little surprise either: Zimbabwe. In Mr Ibrahim’s index, Zimbabwe did a bit better, coming 46th out of the 52 countries assessed. That put it ahead of Congo, Guinea-Bissau (sometimes deemed a narco-state), desolate Chad, repressive Eritrea, the civil-war-ravaged Central African Republic, and Somalia, which is still widely viewed as a failed state.

The WJP report, issued in Washington, counts 18 African countries among those it measures, and uses eight yardsticks to assess how the rule of law is experienced. It seeks to measure constraints on government powers; corruption; the openness of government; fundamental rights; order and security; enforcement of regulations; civil justice; and criminal justice. Mr Ibrahim’s index covers a wider geographical range, including all but three of Africa’s 55 countries, and applies a broader set of criteria. It lumps political participation and human rights into a single category. It also measures safety and the rule of law, sustainable economic opportunity and human development, thus putting greater emphasis on prosperity.

In the WJP index, Ghana comes a notable second, while in the Ibrahim index it places seventh. That marks it out as west Africa’s most creditable country in both listings. Another strong performer is Senegal, which comes an admirable fourth in the law index and ninth in Mr Ibrahim’s table.

One eyebrow-raising result was South Africa’s mediocre performance. Still by far the most sophisticated African country in terms of economic development and in most aspects of the law, it nevertheless comes just third in the World Justice Project’s list and fourth in Mr Ibrahim’s. It is bested in both tables by Botswana and Ghana, perhaps because of a perceived rise in corruption.

Another notable feature of the WJP index is that several countries that foreign investors have been eyeing with high hopes nonetheless perform poorly in terms of the law. Kenya comes 12th, Ethiopia 14th and Nigeria 16th.

Do such tables make any difference to how governments perform? It is hard to say. One struggles to imagine Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s president-for-life, staying up late worrying over his poor performance on the WJP Rule of Law index. Still, no one likes to be named and shamed as crooked and cruel.