By Jacqueline M. Klopp

By 2030, Africa will be a predominantly urban continent. Its growing cities already serve as crucibles of growth, creativity and innovation; providing livelihoods, markets, arts, manufacturing, services, technology, connectivity and education for large numbers of people including those from and in rural areas. Reflecting the strong productivity and creativity of cities, Nairobi metropolitan region is typical in producing roughly 45% of Kenya’s GDP. This means that how Africa’s cities develop will have enormous implications for the future prosperity and wellbeing of the continent as a whole.

As rapid city-building moves forward and the need for critical urban services grows, national governments are borrowing significantly to build urban infrastructure; the transport sector, in particular, is attracting growing attention and investment given the threats of massive congestion, serious air pollution problems and crashes, now one of the top killers of youth. Africa’s urban transport infrastructure and mobility systems are a key part of addressing the growing problems that threaten to stifle urbanization’s benefits. Quite simply, as the American urbanist and journalist Alex Marshall notes, “if we want to shape a city, we have to shape its transportation”.

This raises many critical questions about what kind of city should transportation help shape? What kinds of urban transport infrastructure is needed to create the greatest prosperity, livability and health for Africa’s cities? In what ways can Africa’s urban expansion benefit from 21st-century technologies including the digital revolution?

Currently, in the rush to expand urban roads and highways and develop mass transit systems such as Bus Rapid Transit or rail in Africa, these important questions sometimes get short shrift. In addition, the fact that the majority of Africans rely on walking and some form of public transport- usually “popular transport”-is rarely recognized as a key advantage for future development, providing a real chance to leapfrog from current, congested inequitable and fragmented land use and mobility patterns into transit-oriented, walkable and healthier cities. If this opportunity is ignored, a danger exists that Africa will repeat-at great cost to equity, budgets, public health and economic vitality- the sprawled polluting patterns of automobile-oriented development that characterized much of mid-20th-century experience in other parts of the world.

Sadly, the focus on building highways and high-speed corridors tends to ignore the fact that from Cape Town to Cairo most people rely on walking, motorcycles, bicycles and minibuses to get around. These forms of popular transport move large numbers of people and goods and employ a plethora of workers. While imperfect, this makes African urban life possible and productive. Individuals, companies and cooperatives often organically arrange everything in these systems from setting fares and providing security to determining stops and routes. All these are usually critical government functions; when not provided, popular transport entrepreneurship steps in to provide services and planning.

Given this “informality”, popular transport, while strongly present on the street, is often absent from planning, policy and projects. The ambitious infrastructure investment underway in many African cities is often animated by a 20th-century modernist ideal that envisions eventually replacing these systems with expanded highways, Bus Rapid Transit or commuter rail. While often necessary, these large-scale projects are not sufficient to make cities work well for people and some, like highways carved into dense urban fabric actually contribute to congestion, air pollution and crashes. Overall, by marginalising popular transport and walking in planning, new infrastructure tends to perform poorly and often adversely impacts people using these modes.

Highways designed without considering how most people move tend to be dangerous, adding to already alarmingly high road fatalities in African cities. Similarly, mass transit systems built along corridors tend to poorly integrate with popular mobility systems, which are needed to “feed” these systems passengers. Hence, after a great deal of investment, these systems do not always perform as well as they could which is reflected in the disappointing performance of BRT in many places. Finally, critical services taken for granted in Europe or North America such as basic transit maps and apps –information systems that allow passengers to better plan efficient trips by public transport– are simply missing.

Lack of data on popular transport enables official invisibility of these mobility systems in planning. Data is needed to understand and see popular transport – their networks, dynamics and importance. Without this ability to visualise and analyse these systems, transportation planning is, in effect, looking at the body of the city without understanding the vast, dynamic circulatory system that gives the city life. Working in blindness, planners are more likely to design and implement fragmented, poorly integrated, disruptive and even dangerous transport interventions and infrastructure- costly mistakes in terms of tight budgets and human life and urban vitality.

The Digital Commons

Rallying against this, a “digital commons” movement has emerged in support of better transport planning globally. This movement leverages the digital revolution to build high-quality, open and standardised public transport data for planning, information services and as the basis for moving towards a new mobility paradigm. Within this paradigm, the ability to access a wide suite of high-quality mobility options via a mobile phone becomes a more compelling ideal of freedom than simply owning and using a car.

This transition to freedom of movement by not owning a car but accessing and paying for a choice of multiple transport modes via mobile phone technology is a key step towards more equitable, clean, safe and low emissions cities. African start-ups like Swvl in Cairo, GoMetro in Cape Town and Buupass in Kenya and global companies operating in Africa like Uber and Google are already anticipating and adapting to this trend. This new mobility paradigm means that data and technology are an even more important part of the core infrastructure for urban transportation and mobility.

With high public transport and cellphone use, African cities, are uniquely placed to “leapfrog” or more accurately craft their own pathways into this transition. Indeed, with this vision, civic activists (hacktivists) are using basic GPS-enabled cell phones and other technologies to build high-quality, standardised data for public transport including dominant popular transit modes. This data is made open and shared widely to improve understanding and discussions of how to improve transport planning and build passenger information systems, the stepping stones to a new mobility paradigm.

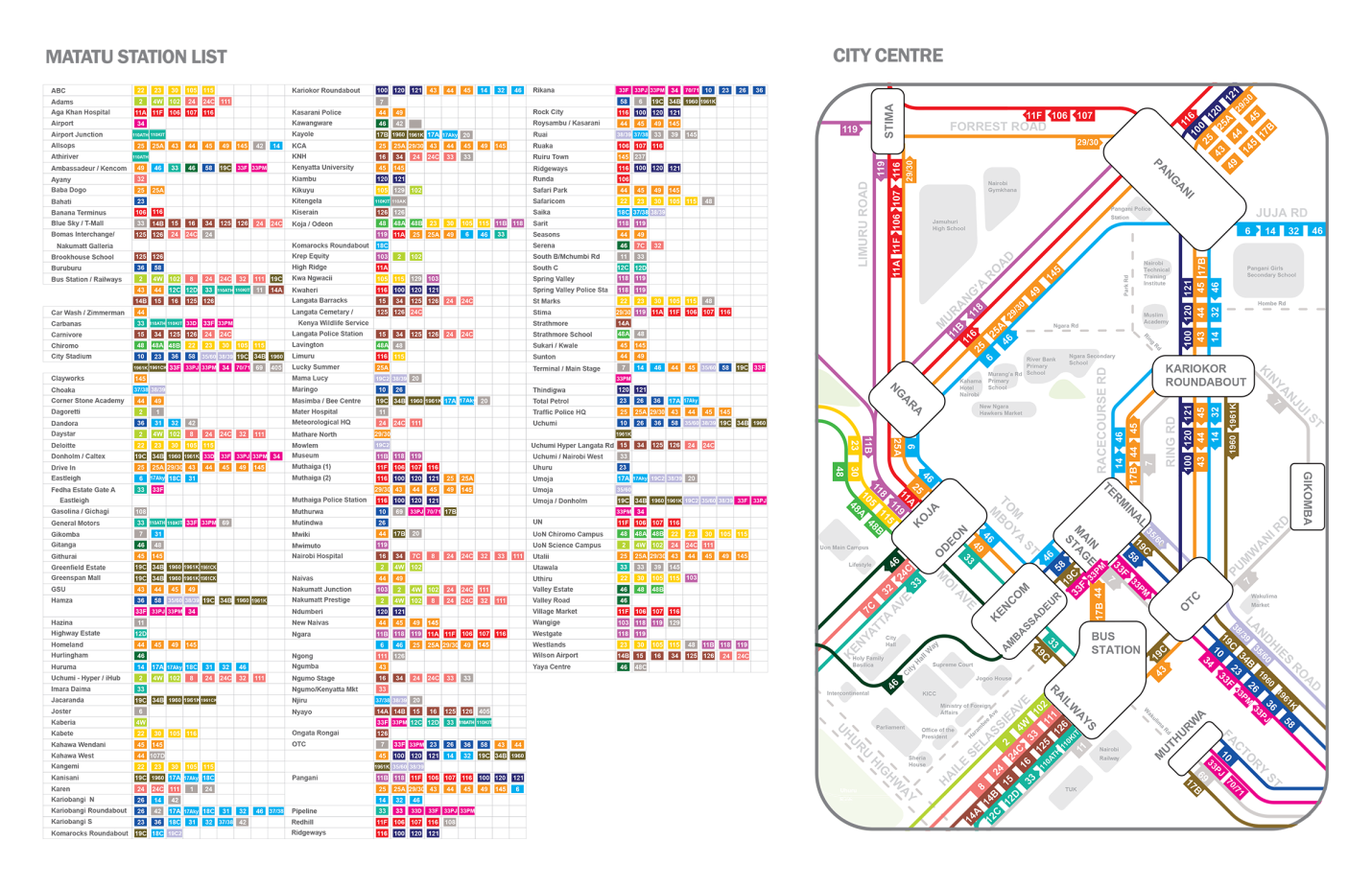

For example, the Digital Matatus project (digitalmatatus.com) a collaboration between the University of Nairobi, Columbia University, MIT and a small design firm Groupshot mapped out Nairobi’s minibus (matatu) routes and stops. By making the data publicly available in a standardised format, the project enables spatial analysis and visualisations including the first, data-based stylised public transit map for a minibus system on the continent and the first city to have matatu data on Google maps.

The DigitalMatatus map and data allow us to see a critical part of Nairobi’s circulatory system. The matatu system is a radial network with all major routes converging on the centre contributing –along with cars– to congestion. Connections cluster at the city centre, and the absence of cross-town routes means passengers must get off and walk a distance to find another matatu to cross the city.

An optimal network for Nairobi would have more of a grid structure and a richer spread along with crosstown routes. As Jarrett Walker, author of Human Transit notes: “This is a common thing that goes wrong in privately evolved systems. Every matatu wants to go downtown because it’s the biggest market, and a matatu driver doesn’t have to be coordinated with anyone else to fill a bus going to and from there.” While these systems generate certain efficiencies, they do not create the best kinds of networks for the city and its residents. This suggests negotiating network reorganisation, using financial support as a lever, could improve public transport significantly along with more localized upgrading of roads, stops and terminals, developing service contracts to improve service and other critical measures.

When matatu data is overlaid with other kinds of data, we can also explore how this mobility system generates access to services and opportunities in a city where only a minority owns cars. For in the end, it is really access we wish to improve not just mobility. The World Bank, for example, was able to use DigitalMatatus data to explore physical access to hospitals in Nairobi generated by the matatu system. The report identified that good physical access is clustered in the centre of the city. Disturbingly, for significant parts of the city, people do not have a hospital within a 30 or even 60-minute matatu ride. This data highlights the ways that transport and land-use are inter-related; the problem of physical access to hospitals in Nairobi can be solved by building more dispersed facilities, encouraging more and better housing in well-serviced areas, redesigning matatu routes or through a combination these and other interventions.

Conclusion

Overall, high-quality, affordable public transport, walkability, accessibility and better land-use and distribution of (affordable and quality) services are all critical steps towards a more equitable, inclusive and productive city. To intervene intelligently and advocate for change, however, we need to be able to see, analyze and also discuss these inter-relations and advocate for holistic data-driven policies and projects. This is also why open data and building a “digital commons” is so critical-it allows more actors to build, analyse and even correct this fundamental resource for cities.

Beyond creating tools for understanding, seeing and refashioning the city, this new open data creates a very important basic service for citizens; passenger information. Passengers can look at a map or on a transit app and see how to get from one place to another using the minibus system. Digitalmatatus data is on Google Maps and other platforms allowing trip planning for matatus, information not available for the vast number of cities in the world.

Evidence is growing that this kind of trip planning information can help people make more efficient trips and, when coupled with real-time information, reduce waiting. This, in turn, improves the way passengers interact and feel about public transport. Infrastructure improvements are still very necessary, of course, especially in support of walking or non-motorized transport but building these information systems including ways for citizens to give feedback helps advocate for these improvements and move closer to a 21st-century mobility paradigm. Other measures such as minibus upgrading and electrification or cleaner fuels are also needed but almost every intervention requires some critical data as part of the base infrastructure.

Africa’s rapidly growing cities have an opportunity to leverage technology to build critical data infrastructure, not only for minibuses but other forms of public and popular transport as well. Across the continent, in more and more cities, government officials, civil society and tech “hacktivists” are leveraging new technological capabilities to build critical open data infrastructures for transforming urban mobility. Motivating this work is the very real possibility of building transit-oriented, safer, cleaner and more productive African urban futures.

Twitter: @jmklopp1

Facebook: Jacqueline Klopp