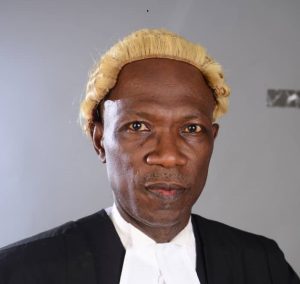

Africa’s global partnerships are often framed as mutually beneficial, yet beneath the surface lie legal and economic imbalances that shape the continent’s trajectory. With decades of experience in international law, Emeka U. Opara, Principal Attorney at The City of Law, a global firm based in Lagos, Nigeria, offers a critical analysis of Africa’s trade agreements, governance challenges, and diplomatic negotiations. Focusing on legal frameworks, he highlights structural weaknesses that leave African nations vulnerable and outlines strategic steps to secure fairer deals, uphold sovereignty, and drive sustainable growth. His insights challenge conventional narratives and propose a roadmap for Africa to redefine its role in global trade.

Africa and the European Union

With your extensive background in international law, how do you assess the EU’s role in Africa’s economic and political development, particularly through agreements like the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs)? Do these agreements foster real progress, or do they reinforce dependency?

I have a foundational understanding of the World Trade Organization (WTO). During my Master’s programme in International Law at the University of Leiden, I took a course on WTO Law. Though I did not sit for the exam, I received a certificate of attendance.

Regarding your question, I would approach it with caution. On paper, EPAs appear beneficial, promising to enhance trade between Africa and the EU. However, in practice, EU states maximise their advantages while offering minimal benefits to African countries. The EU has two main priorities: first, ensuring a steady flow of raw materials from Africa; and second, enforcing stringent standards on these exports. While these priorities may not be explicitly stated in agreements, they are evident in practice. I do not entirely blame the EU—it is natural for states to negotiate in their own interests. However, many African governments, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, fail to do the same. This imbalance makes EPAs seem benign at first glance but problematic upon deeper examination.

Take Nigeria, for example. Two major obstacles hinder its success in trade agreements. First, the country does not deploy the right expertise. When selecting trade delegates, the focus is often on political or ethnic considerations rather than expertise in international trade law. Second, Nigeria lacks the capacity to compete effectively in global markets. We must empower our industries to go beyond raw materials and move up the value chain. This requires targeted policies, investments in education, and reforms to ensure that international trade law is a fundamental part of legal education. European countries have long positioned themselves for global trade through structured education and policy alignment—Africa must do the same.

Another critical issue is Nigeria’s outdated Customs and Excise Act. This colonial-era legislation is one of the most obstructive laws in our statute books. It was created under the assumption that public officers would adhere strictly to regulations, but today, corruption undermines its effectiveness. Customs, immigration, and other trade-related agencies must undergo a comprehensive reform to align with modern economic realities.

If these foundational issues are addressed, Nigeria and the broader West African region could unlock significant trade potential. Currently, Nigeria captures less than 10% of its possible trade benefits within West Africa alone. In the long run, once African nations develop their capacity, the EU will be compelled to renegotiate EPAs on a more equal footing. This will reveal the true nature of these agreements—structured primarily for European gains rather than Africa’s prosperity.

While the EU advocates for human rights and democracy in Africa, critics argue that its policies often carry neocolonial undertones. How can African nations ensure equitable partnerships while safeguarding their sovereignty and policy independence?

Your premise is entirely accurate. However, African nations must also acknowledge their role in perpetuating these imbalances. The EU’s influence can only succeed to the extent that Africa allows it. To resist unfair policies, Africa must project strength—a continent defined by innovation, education, and competent governance, rather than one weighed down by corruption and instability.

How can Africa secure equitable partnerships while continuing with outdated governance models? Nigeria, for example, must address illiteracy, governance failures, and policy inconsistencies. Leadership should prioritise development over ethnic or religious biases. There is a stark difference between genuine faith and religious extremism that hinders progress. The same governors who halt education for religious observances are often those who embezzle funds meant for improving schools.

During President Goodluck Jonathan’s administration, certain governors acted in ways that compromised national stability, and the United States engaged with them diplomatically. Had Nigerian leadership been stronger and more unified, external interference would have been less effective.

To negotiate effectively with the EU or any global power, Africa must first address its internal challenges. A united, educated, and economically empowered Africa will command respect in international negotiations, ensuring that partnerships are built on fairness rather than dependency.

Migration Policies Between Africa and the EU

Migration policies between Africa and the European Union (EU) remain contentious. While Europe continues to tighten its borders, Africa grapples with the challenges of brain drain. How can legal frameworks be strengthened to address these migration challenges in a way that benefits both regions?

The core issue is not merely legal but strategic. African states must insist on fair treatment of their citizens and apply the principle of reciprocity in migration negotiations. Notably, former Nigerian Head of State, Olusegun Obasanjo, implemented policies that bolstered national pride and reinforced the country’s international standing. Similarly, while African migrants face strict entry barriers in the EU, European companies operate freely across Africa. By leveraging their economic significance, African nations can advocate for better treatment of their citizens at EU borders and within its member states.

However, it is ultimately a sovereign right of any country to regulate entry. Over time, restrictive EU policies may prove counterproductive. If African nations implement sustained good governance reforms over a decade, improving economic conditions and creating opportunities at home, migration patterns could shift. In such a scenario, fewer Africans would feel compelled to seek opportunities abroad under difficult conditions.

Africa and the United States

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) has shaped US-Africa trade relations but is set to expire in 2025. What legal and economic strategies should African nations adopt to reduce reliance on AGOA and establish sustainable trade with the US?

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) has been a cornerstone of US-Africa trade relations, but with its scheduled expiration in 2025, African nations must develop sustainable trade strategies beyond AGOA.

To achieve this, African states should:

- Enhance Value Addition – Raw materials should only be exported after reaching at least a median stage in the value chain to maximise economic benefits.

- Avoid Internal Sabotage – Africa’s biggest challenge often comes from within. Countries like Nigeria must take a leadership role in fostering continental trade rather than inadvertently undermining it.

- Recognise the Political Nature of Trade – While trade and politics are often presented as separate, Western powers, including the US, use political leverage to shape economic realities in Africa. African nations must push back against economic and political blackmail that stifles local industries.

Furthermore, diplomatic appointments play a crucial role in trade strategy. African trade attachés in key global markets, such as New York, must be selected based on expertise rather than political patronage. These representatives should possess deep knowledge of international trade and economic intelligence, ensuring they contribute meaningfully to trade negotiations and policy decisions. Currently, the selection and training processes for such officials remain weak, raising concerns about their effectiveness.

US Sanctions on Africa: Effectiveness and Impact

The US frequently imposes sanctions on African nations over alleged human rights violations and governance failures. Are these sanctions effective in promoting accountability, or do they erode African sovereignty and economic stability?

The United States frequently imposes sanctions on African nations for alleged human rights violations and governance failures. However, the effectiveness of these sanctions in promoting accountability remains debatable.

Recent revelations have highlighted inconsistencies in US foreign policy towards Africa. The imposition of sanctions, while advocating for democracy, appears contradictory when juxtaposed with instances where Western powers influence electoral outcomes. For example, recently declassified documents have raised questions about external involvement in Nigeria’s 2023 elections.

Ultimately, governance reforms must originate from within Africa. Citizens must demand accountability and reject leaders who rise to power through ethnic or political manipulation rather than merit. A governance culture rooted in transparency and competence is essential for Africa’s long-term stability and development.

Navigating Global Power Struggles: Africa, the US, and China

As China’s influence in Africa grows, the US has sought to counterbalance it through initiatives like Prosper Africa. How can African nations navigate these competing global interests while safeguarding their strategic priorities?

Africa’s geopolitical significance stems from three main factors:

- Abundant Natural Resources – Africa remains a key supplier of minerals essential for global industries.

- Labour Market – The continent offers a vast workforce, often at lower costs.

- Governance Deficiencies – Weak institutions make it easier for external actors to exert influence.

To shift from being a geopolitical battleground to an economic powerhouse, African nations must prioritise:

- Infrastructure Development – Investments in energy and transportation will drive industrialisation.

- Workforce Protection – Policies must safeguard African workers in foreign-owned enterprises.

- Strategic Diplomacy – African leaders must negotiate from a position of strength, ensuring mutually beneficial partnerships rather than dependency.

With a decade of sustained reforms, Africa could reposition itself as a global player rather than a passive recipient of foreign influence.

Strengthening Democracy in Africa: Legal and Structural Reforms

Despite the existence of legal frameworks supporting democracy, challenges such as electoral fraud, judicial interference, and prolonged presidential terms persist across Africa. What structural reforms are necessary to reinforce democratic governance?

Judicial reform remains a critical issue. Professor Chidi Odinkalu, a prominent advocate for legal reforms in Nigeria and across Africa, has repeatedly highlighted the need for judicial independence. His advocacy has made him both a respected voice and a controversial figure among judicial elites.

Electoral fraud in Nigeria, for instance, has evolved over time, becoming more sophisticated with each election cycle. The real turning point will come when an African head of state demonstrates a genuine commitment to electoral integrity—even at the cost of personal political loss. Leadership by example will set the precedent for credible elections.

Additionally, Africa must develop a governance model tailored to its unique socio-political realities. The American presidential system, which grants extensive executive powers, may not be entirely suitable for African nations with weaker institutional checks. A hybrid model, blending elements of the US and UK systems while incorporating African cultural governance structures, could be more effective.

Ultimately, strengthening democracy in Africa requires more than just legal reforms—it demands a fundamental shift in leadership culture and political accountability.

Strengthening Africa’s Human Rights Framework

The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights has been criticised for its weak enforcement mechanisms. What legal reforms could enhance Africa’s human rights framework and ensure effective enforcement?

Certain provisions in the Charter are ambiguously worded, allowing for divergent interpretations. Nevertheless, despite these challenges, the African Court has managed to develop some jurisprudence based on the Charter.

To improve enforcement, the Charter could be amended, or an entirely new treaty could be negotiated. However, a major concern is that a new treaty may not garner the same level of support as the existing one, despite its implementation challenges. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides provisions that address situations where some signatories of an existing treaty refuse to accept a new one or certain provisions of it. Articles 39, 40, and 41 of the Vienna Convention specifically outline the procedures for treaty modifications and adaptations.

Safeguarding Judicial Independence in Africa

Judicial independence remains a critical challenge in many African democracies, with allegations of executive interference in court rulings. What legal safeguards can be implemented to uphold judicial integrity and the rule of law?

A key reform would be to remove the Chief Judge from heading both the judicial disciplinary body and the judicial appointment committee. Additionally, executive influence over judicial appointments should be eliminated. The trend of appointing judges based on political affiliations—such as the selection of spouses of politicians—should be replaced with a more transparent, merit-based system.

The Bar should play a more significant role in the selection process, as legal practitioners have a deeper understanding of who is both competent and ethical. Only individuals with sound legal and ethical standards can make fair and impartial judges.

However, the Bar itself faces challenges. While the judiciary is perceived as being largely under executive control, the Bar has, in some cases, become a tool for political interests. There is a growing culture of silence, with reports of senior judges subtly warning lawyers that their prospects for attaining the rank of Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) could be jeopardised if they openly criticise the judiciary. The Body of Senior Advocates of Nigeria (BOSAN) now appears to be an institution reluctant to challenge judicial misconduct. To address this, a more rigorous disciplinary mechanism should be established to hold both judges and lawyers accountable.

Africa’s Engagement with the ICC and the Case for Regional Accountability

International courts, particularly the International Criminal Court (ICC), have faced accusations of disproportionately targeting African leaders. Should Africa develop its own regional accountability mechanisms, or is continued engagement with the ICC—under reformed conditions—a better path forward?

As part of the global legal system, Africa cannot afford to completely disengage from the ICC. The ICC cannot realistically prosecute every violation of international humanitarian law, the laws of war, or human rights abuses during conflicts. Thus, establishing a regional tribunal to address egregious human rights violations, particularly during armed conflicts, would be a logical step.

However, the ICC remains necessary. In many cases, African leaders accused of serious crimes are beyond the reach of national or regional judicial mechanisms, making ICC intervention essential. While Europe has largely moved beyond internal conflicts akin to Africa’s, historical factors such as colonial-era partitions continue to fuel tensions across the continent.

The ICC itself requires reforms. Over the past decade, concerns have emerged regarding the influence of religious and ideological biases within the court, including allegations of anti-Semitism. Such factors could undermine the ICC’s mission more than the perception that it disproportionately targets African leaders. A reformed ICC, coupled with a robust African regional accountability mechanism, could provide a balanced approach to addressing human rights violations on the continent.

A seasoned legal professional with over three decades of distinguished practice, Emeka U. Opara is an accomplished advocate, legal strategist, and policy expert with a strong track record in public international law, human rights, and institutional legal frameworks. With an unwavering commitment to justice and an exceptional ability to articulate compelling legal arguments, he has consistently delivered groundbreaking legal solutions both in private practice and public service.

Emeka U. Opara is widely recognised for his meticulous legal drafting, courtroom advocacy, and innovative approach to dispute resolution. His tenure as Senior Special Assistant (Legal Matters) to the Governor of Imo State saw him spearheading executive bills and key policy initiatives. As Principal Attorney at The City of Law, he has handled complex litigation, high-profile negotiations, and corporate advisory services with a commitment to ethical and impactful legal practice.

Its about The Law, the Deals, and the Future as Emeka U. Opara Dissects Africa’s Global Partnerships and Prospects

Its about The Law, the Deals, and the Future as Emeka U. Opara Dissects Africa’s Global Partnerships and Prospects