Mali is a vast, landlocked country in the heart of the Sahel region. It has a low-income economy that is undiversified and vulnerable to commodity fluctuations. Social indicators are among the lowest in the world.

The country ranks 184 out of 189 on UNDP’s 2019, Human Development Index and faces serious challenges in the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

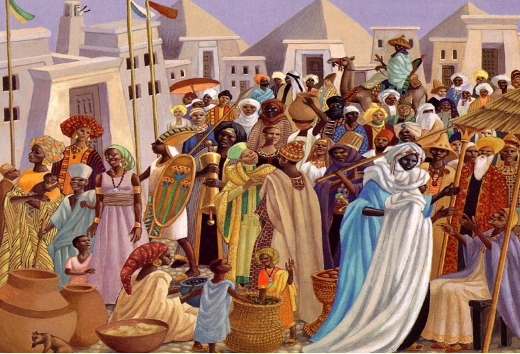

The top search results for Mali online are often stories and images that portray the West Sahelian state in a negative light, stories of the seemingly unending crisis and insecurity, tales of poverty, starvation, and lack of education, all of which are a result of years of political unrest.

The top search results for Mali online are often stories and images that portray the West Sahelian state in a negative light, stories of the seemingly unending crisis and insecurity, tales of poverty, starvation, and lack of education, all of which are a result of years of political unrest.

Indeed, these stories are true, Mali has been plagued by insecurity for quite a while. But what is not true is that the global media portrayed a single story regarding the landlocked country. The stereotypic narrative of Mali as being habitually unsafe and impoverished is incomplete and critically misleading.

Currently, Mali is making tangible practical efforts to transcend its challenges. Malians are building businesses, establishing start-ups, and creating evolutionary innovations that are steadily improving and reviving the country’s economy. With the increasing presence of innovation centres and entrepreneurial hubs, there is a new trend of youths becoming entrepreneurs, all of whom are part of the new dynamic for the country.

Here are some of Mali’s evolutionary innovations of the new evolving Mali. There have been individuals helping in the improvement of, innovations in agriculture, education, technology, and fashion among others, all in the renaissance of the new Mali.

With the country’s literacy level at a meagre 40 per cent, Mamadou Gouro Sidibe is filling a void in the country’s social media and digital space as most Malians cannot access popular social networks like Facebook and Twitter.

The World’s First vocal social network, a platform where users communicate via voice recordings in their local languages. “Approximately only 20 per cent of Malian people have access to digital services due to the low level of literacy, that’s why I created this vocal social network which speaks local languages in order to give Malians access to digital tools and also to serve as a starting point for systematic development”, says Sidibe.

Today, there are over 40 thousand users on Lenali from all over the world. “we mostly have Malian users because we started here but we also have users from France, Senegal and Burkina Faso, and so on. People can access the service from anywhere,” he said.

Thanks to the Malian government, Mamadou has had the opportunity to be at the CES show in Las Vegas for four months for a showcase of Lenali. According to him, being in Las Vegas brought him in contact with potential partners and investors with whom he is in discussion and quite optimistic about the outcome.

Thanks to the Malian government, Mamadou has had the opportunity to be at the CES show in Las Vegas for four months for a showcase of Lenali. According to him, being in Las Vegas brought him in contact with potential partners and investors with whom he is in discussion and quite optimistic about the outcome.

“African youth are often criticized as being lazy. That’s not true. African youths are creating a lot of amazing projects across the board. We need the youth, to realize the fact that if our youth are equipped with the right tools and resources they can do anything. Do not blame equip them” Says Makhan Sacko (Project Manager, Impact Hub, Bamako).

When Impact Hub (IH) opened in Bamako in 2016, there were no other hubs, but in two years, that has changed with the city boasting 10 hubs currently. Part innovation Lab, part business incubator, Part Social enterprise community centre, the goal of Impact Hub is to create a work environment that inspires and motivates, a space where businesses can make connections, learn from each other and develop new skills.

Located in over 80 countries around the world, Impact Hub Bamako is the first of the network in Francophone Africa. Here, the hub trains entrepreneurs, offer acceleration programs to early-stage entrepreneurs and also provides an affordable co-working space. It’s basically a business model for innovation centres.

“However, our specificity is that we are more focused on agribusiness,” says Makhan Sacko. Mali is an agricultural country with more than 80% of the population in agriculture, hence it makes sense that the Hub chooses to focus on that sector. Plus Mali’s most successful hubs are agribusiness centred.

“However, our specificity is that we are more focused on agribusiness,” says Makhan Sacko. Mali is an agricultural country with more than 80% of the population in agriculture, hence it makes sense that the Hub chooses to focus on that sector. Plus Mali’s most successful hubs are agribusiness centred.

A centre like IH has influenced the growing number of youth entrepreneurs in Mali and other Francophone African countries, a trend that was lacking a few years ago.

“Entrepreneurship was not part of the options for youths in Francophone Africa, Mali, and Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, we were lagging behind compared to countries like Nigeria and Ghana,” Sacko said. “Now there is increased awareness on the benefits of entrepreneurship and more opportunities for youths, hence an increasing interest of youth in entrepreneurship,” he added.

The Malian government is also playing a role in encouraging this new trend. Having realized the fact that entrepreneurship is a solution to youth unemployment, the government is collaborating with hubs, organizing pitch programs, financing projects in conjunction with the world bank and also working toward opening a hub as well. Sacko believes the government can and should do more, particularly in building an ecosystem.

The Malian government is also playing a role in encouraging this new trend. Having realized the fact that entrepreneurship is a solution to youth unemployment, the government is collaborating with hubs, organizing pitch programs, financing projects in conjunction with the world bank and also working toward opening a hub as well. Sacko believes the government can and should do more, particularly in building an ecosystem.

“It’s not just about financing the youth, it’s building an ecosystem. Because even in cases where you have banks and financing, the right human resources are needed, and education is needed. The government needs to invest in human capital and also create a market that will facilitate the access of entrepreneurs.” Sacko said. “Because, even if you finance agribusiness, if the entrepreneur does not have the right skill and doesn’t have access to the markets, it doesn’t really make sense. So what the government can do is to strengthen the ecosystem, not just in financing but in infrastructure as well” he added

A concoction of baobab, tamarin, zaban, kinkeliba, ginger, and hibiscus are what make up the range of one of Mali’s most prominent juices – Zaaban. Zaaban is an all-natural blend of locally grown fruits, flowers, and herbs in Mali. The brand’s CEO 28-year Aissata Diakite is one of many returnees who seeks to invest in and promote the Malian economy.

As she said, “My dream is for Zaaban to be the Coke of Africa.” For her, the thought and choice to launch a juice company in Mali came easy because Mali grows a variety of fruits and herbs, particularly in Mopti where she comes from. She has therefore partnered with farmers from Mopti to Kayes to grow and supply what she needs to make juices. Zaaban produces over a thousand bottles of juices daily, one of which is sold at 500 CFA frans.

Only 40% of the products are sold in Mali, 10% is exported to France and the rest to other African countries, Ivory Coast, Benin, Togo and Burkina Faso. They also cater for hotels, restaurants and supermarkets, supplying them as wholesalers and to consume at home and at events on demand. As an entrepreneur, Aissata has about 80 employees on her payroll, excluding the large network of farmers she works with across Mali.

Only 40% of the products are sold in Mali, 10% is exported to France and the rest to other African countries, Ivory Coast, Benin, Togo and Burkina Faso. They also cater for hotels, restaurants and supermarkets, supplying them as wholesalers and to consume at home and at events on demand. As an entrepreneur, Aissata has about 80 employees on her payroll, excluding the large network of farmers she works with across Mali.

It is sad to realize that the people of Mali who so ably met the challenges of their past and are fighting to evolve are amongst the poorest countries in west Africa. It is to be hoped that both urban and rural people can combine their ancient skills with modern technology to reach higher standards of living in the years ahead.