Khadija Yusra Sanusi

Undoubtedly, the world was unprepared for Coronavirus disease (COVID19). It’s arguable that developing countries were even more so for reasons such as lack of infrastructure, weak healthcare systems, significant doctor-to-patient ratio and minimal to absence of government funding for healthcare. In addition, the COVID19 pandemic gave rise to a rape epidemic (with the lockdown used as a front for sexual violence at home), an increase in reported cases of domestic violence and a dire need for strong mental health intervention, especially in developing countries.

The first case of COVID19 in Nigeria I heard was that of an Italian citizen who worked in Lagos. In February 2020, he returned from Milan and was soon after confirmed with the virus. Having one case of airborne disease in a country that ranks among the top 10 most populated countries in the world was too many. For Nigeria especially – with its low coverage of health insurance, minimal access to essential medicines (36% reported accessibility in private facilities and 26% for public facilities), and inequitable spatial distribution of health services and facilities across the country – it was a deathly epidemic.

In Nigeria, there is no dedicated healthcare industrialization and trade policy focused on the health sector due to inadequate storage conditions during shipping, in warehouses, hospitals, pharmacies and homes and a lack of supply chain infrastructure. In addition, there is limited technology for anti-counterfeiting, inventory management, training apps used for Continuous Professional Development (CPD), as well as a lack of skilled technical personnel in drug development and manufacturing. Most employees in the local pharmaceutical manufacturing sector are semi-skilled workers who acquire their skills on the job. Above that, there is low healthcare funding by the federal government, because of which 71% of health expenditure is out of pocket. This is a staggering number for a country with 40% of its population living below the poverty line, which amounts to more than 82 million Nigerians living on less than $1 a day.

The impact of COVID19, especially psychologically, could not have been predicted. “The “unknown” is usually a mental stressor as the mind is left to fill the gaps with the worst-case scenario more often than not,” Hauwa Ojeifo, sexual violence and mental health activist and Executive Director of She Writes Woman, told African Leadership Magazine. She explained that the pandemic came as an existential shock partly because there was no end in sight. The uncertainty about the reopening of the economy and the return to everyday life led to business and economic pressure, grief and threat of life.

At the height of it all, countries were reporting hundreds of cases and taking pre-emptive measures such as shutting down borders and putting their citizens on lockdown. The isolation from society, coupled with hyper-information of increasing cases and death toll across the globe, had its own psychological impact. As Ojeifo explained, “in a situation where your movement is restricted, your trauma response outlets are also restricted. ‘Fight or flight’ will have to take place with little or no room for movement and expression, as was the case during the lockdown.” This means a restricted combination of uncertainties, grief, loss anxiety and depression that can’t be properly navigated, leading to a hyper increase of cortisol (the stress hormone). “We aren’t wired for such a time,” Ojeifo adds. “We are hardwired for connection, community, and certainty.”

There is a pressing need for stronger health systems in developing countries. Nigeria has been ranked among the worst healthcare network in the world, taking the 142nd position out of 195 countries ranked. Hannatu Ahmad Ibrahim, the intern at National Hospital Abuja, told African Leadership Magazine that “the Nigerian healthcare system is poorly developed; there is lack of awareness, inadequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs) and not enough isolation centres. It has failed woefully in providing care to both care workers and patients. But all hope is not lost, we can do better.” She explained that the main factor that contributed to the spread of the virus was people not believing that it existed. To be fair, both governmental and private institutions tried to create awareness about COVID19, but people simply refused to believe it was real.

In a conversation with The Voice in 2020, one of Nigeria’s leading public health campaigners, Niniola Williams, explained that culture affects the way we see and interact with modern medicine. It is hard for Nigerians to trust doctors, she said, because when they go to their local healthcare facility, the doctor is often unavailable and there are no medical supplies; you would have to go and buy the PPEs such as gloves the doctors need to attend to you. Because of this, many people would opt not to go to hospitals when they are ill, which will play into the spread of the disease, making it more viral than contained.

For this and several other reasons, countries were unprepared for COVID19. But these are factors that can be addressed and resolved in preparation for the next pandemic. According to Amanda McClelland, Senior Vice President of the prevent epidemics team at Resolve to Save Lives, an initiative of Vital Strategies, there are several ways in which countries can prepare for the next pandemic. They must have an effective system to detect, rapidly investigate and verify new cases. They should also build essential capacities related to surveillance, laboratories, a trained workforce and emergency response by allocating financial and human response to ensure the containment of important cases and mitigate the social, economic and health impacts of all parts of the community. She also argues that countries must have adequate supply chains of essential medicines and infection prevention and control equipment; trained health workers who can respond safely and are able to isolate and care for the sick; and the ability to communicate about the disease and combat misinformation quickly among all parts of the community. Furthermore, she believes governments, civil societies and international partners should support investments to prepare counties for the management of outbreaks and protection of lives.

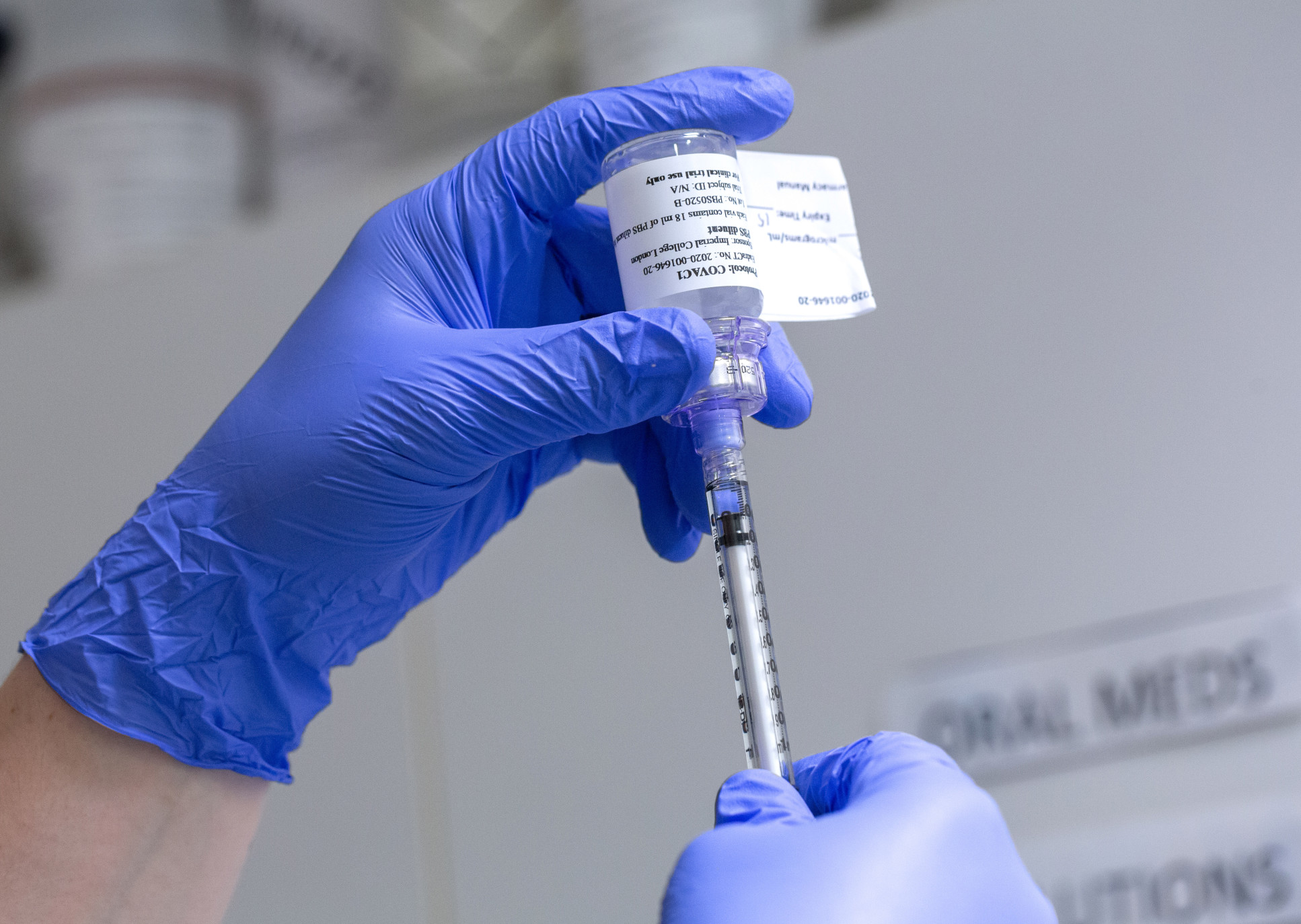

Should countries have to close their borders or citizens have to go on lockdown, developing countries need a robust healthcare system to prevent, find and stop diseases. For stronger healthcare systems, Nigeria needs many reforms. It requires health insurance coverage; easier access to and stockpiling of medicine and antiviral drugs; better infrastructure and well-equipped health facilities; health-focused trade policy and industrialization; well-skilled technical personnel in drug development and manufacturing; active strategies and well-resourced healthcare organizations; huge investments in the NCDC; and technological advancements in the health sector. In many of its sectors, including health, Nigeria relies heavily on imports, especially from China. A good strategy could also be to restrict importations of medical supplies and for the government to fund organizations that seek to develop and manufacture good quality medical supplies. This can be done slowly – first with everyday PPEs, until Nigeria can manufacture more complex medical supplies such as vaccines.

Poor healthcare has a huge impact on the economy. The Nigerian federal government provides loans for people through a parastatal called NIRSAL to fund local start-ups. However, for many people, insecurity has been a hindrance. Businesses can’t thrive where there is inadequate healthcare and insecurity; the cost is simply too high. With insecurity, inadequate police and unreliable healthcare services and facilities, Nigerian businesses are not able to thrive, and people are not able to pay taxes, which the government can use to fund the revampment of the different sectors, especially health. They always say, “Health is Wealth”; it took a global pandemic to show us just how true that is.