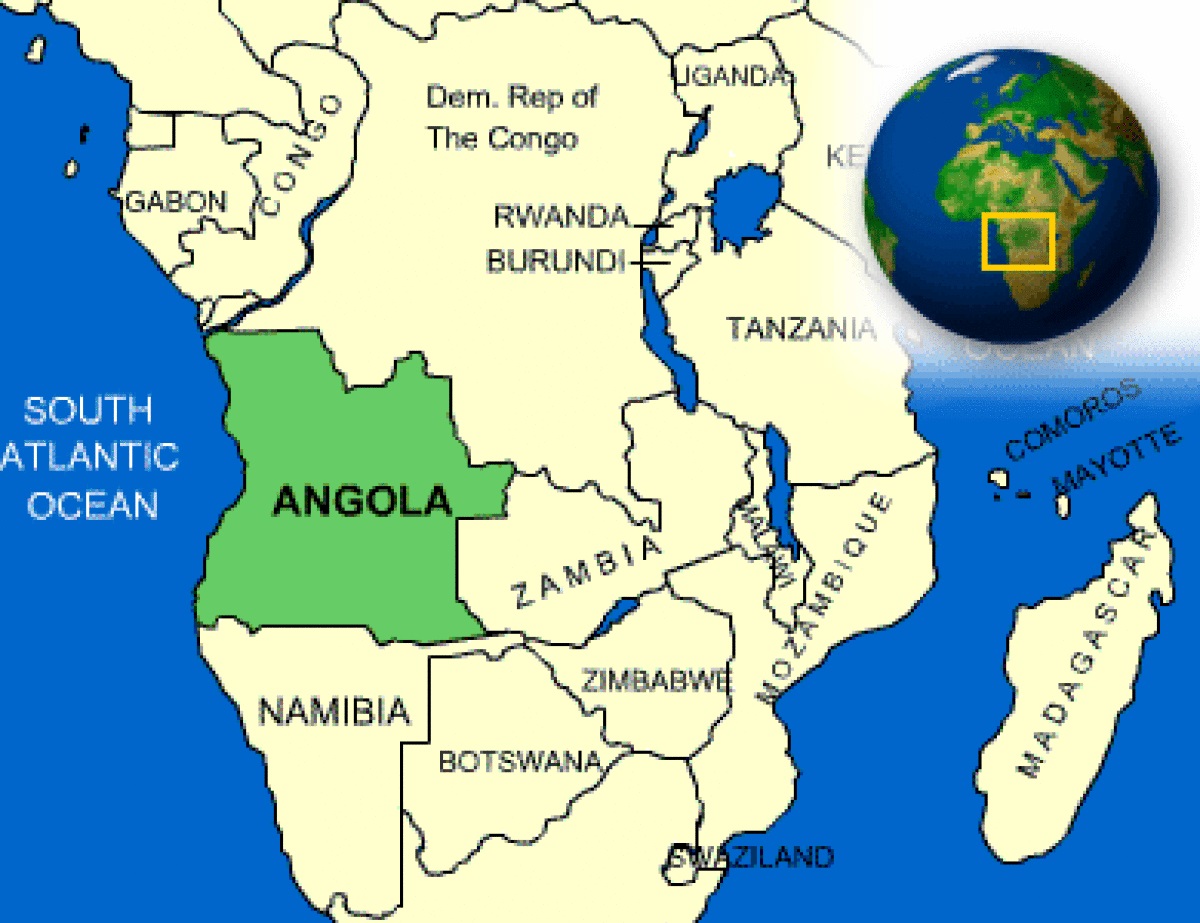

Angola, a country in the southern part of Africa, formerly a slave harbour, has become a central figure of Africa’s economic appeal. The country with vast mineral resources like petroleum deposits and billions of cubic metres of gas is a significant member of the OPEC, a body that convenes most petroleum product-exporting nation.

The post historic emigration of the colonial Portuguese to Angola to establish farms and plantations (fazendas), to grow cash crops for export, saw the concentration of interest and exploitation of the citizens of this dwelling. Although these farms were only partially successful before World War II, they formed the basis for the economic growth that shaped Angola’s economy in the late 1980s. Many consider it preposterous to say the Angolan economy was built by the natives, but the Portuguese government was concerned primarily with keeping its colonies self-sufficient and therefore invested little capital in Angola’s local economy as evidenced in the lack of roads until the mid-1920s, and the hesitancy in the completion of the Benguela Railway until 1929. However, the liberalization of global trade and fair practices gave way to a complete transformation. Insomuch that, in the 1960s, a fruitful commercial agricultural sector, a nascent manufacturing industry and a prospective global mineral and petroleum production enterprise had all emerged.

According to a research facilitated by the US library of congress “By 1976, these encouraging developments had been reversed. The economy was in complete disarray in the aftermath of the war of independence and the subsequent internal fighting of the liberation movements. According to the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola-Workers’ Party (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola-Partido de Trabalho–MPLA-PT), in August 1976 more than 80 percent of the agricultural plantations had been abandoned by their Portuguese owners; only 284 out of 692 factories continued to operate; more than 30,000 medium-level and high-level managers, technicians, and skilled workers had left the country; and 2,500 enterprises had been closed (75 percent of which had been abandoned by their owners). Furthermore, only 8,000 vehicles remained out of 153,000 registered, dozens of bridges had been destroyed, the trading network was disrupted, administrative services did not exist, and files and studies were missing.” These economic challenges of the country can also be traced to the vestiges of the Portuguese colonial development.

Despite the Angolan economy impressing by a fickle of growth signs by 1960, most developments had originated of recent albeit very precariously. Angola’s industries in the past have depended parasitically on Portugal – the country’s development bête noire – for the skillsets and capital required to finance its market operations.

In 2016, a stock exchange called BODIVA (Angola Securities and Debt Stock Exchange, in English) began with securities and bonds being traded officially in 2017. Along with Bodiva, came a new private investment law (Number 14/15) that raises taxes on early repatriation of profits and dividends, distinguishes between foreign and domestic investors, and requires local participation (at least 35% of total investment) to enter key sectors such as electricity and water; tourism and hospitality; transportation and logistics; telecommunications and information technology; construction; and media. Corporate income taxes were also reduced from 35% to 30%. Repatriated profits tax range between 15% and 50% depending on how much and how soon initial investments are withdrawn. Finally, tax breaks are granted to investors who create local jobs, generate higher export receipts, and use local inputs in their business processes. The private investment law, which requires foreign investors to partner with local companies and employ a certain amount of Angolans in critical sectors, still deters a number of investors from seeking opportunities in the country. The National Agency for Investment Promotion and Export (APIEX) was created to stimulate economic growth, diversify the economy, and expand private sector participation in Angola’s economy.

The majority of FDI in Angola comes from China, the United States, France and the Netherlands. Angola was the second largest receiver of Export-Import Bank of China (Exim) loans with a total of USD 6.9 billion, according to John Hopkins University’s China-Africa Research Initiative. Nevertheless, low oil prices and their impact in business and halted construction projects forced tens of thousands of Chinese to leave the country. Angola currently has 50,000 Chinese workers and business owners, barely a quarter compared to four years ago. Bank of China Ltd. plans to open a branch in Angola to facilitate Chinese investment.

The majority of FDI in Angola comes from China, the United States, France and the Netherlands. Angola was the second largest receiver of Export-Import Bank of China (Exim) loans with a total of USD 6.9 billion, according to John Hopkins University’s China-Africa Research Initiative. Nevertheless, low oil prices and their impact in business and halted construction projects forced tens of thousands of Chinese to leave the country. Angola currently has 50,000 Chinese workers and business owners, barely a quarter compared to four years ago. Bank of China Ltd. plans to open a branch in Angola to facilitate Chinese investment.

Cobalt, a U.S.-based oil company, filed for arbitration with a USD 2 billion suit against Angola’s Sonangol after license extension negotiation for two deepwater blocks broke down in 2017. This could prevent new investors from trusting joint ventures for oil exploitation. The Angolan government is negotiating a tax reform with Chevron in order for the company to invest in the country.

In the investment outlook,

- There are 23 new diamond, gold, phosphate, iron ore, copper, and natural stone explorations,

- Japan conducted a feasibility study for cotton production in northern Malanie.

- Biocom, a partnership between state-owned oil company Sonangol, the government investment fund Cochan, and Brazil’s Odebrecht, set an aggressive deadline to produce 256,000 tonnes of sugar by 2020 in its 1 million acre farm (this would provide for 50% of Angola’s domestic consumption). 33,000 cubic metres of ethanol and 235,000 MW of electricity are also foreseen.

- The iron and steel sector, a joint venture between Ferrangol, the Cuando Cubando Mining Company, and Brazilian Modulax will mine iron ore in Cutato; the iron ore mines in this region have been idle since the 1970s. This iron ore will be used to produce pig iron, requiring USD 199.5 million, and including the construction of a blast furnace, a crushing plant, and charcoal production plants.

Although the negative factor to foreign investment is the high costs of entry to the market, it is overshadowed by strong points such as the asset-based economic built of the country, one of the fastest growing economies in the world, political and economic stability, a large and competitive population on the continent, which makes the country the third largest market in sub-Saharan Africa, a very substantial natural resource deposits, for the financing of large projects, and a high growth potential for the non-oil sectors such as construction and tourism.

Bilateral Investment Conventions Signed by Angola, the Angolan government is disposed to foreign direct investment, which is seen as a factor in diversifying the economy outside the oil and gas industry. Investors, foreign or not, have the same right of access to incentives. However, the policy of “Angolanisation” aims to encourage the employment of nationals and incorporating them into the growing economy to forestall restiveness and the myriad of unintended crises resulting from unemployment.