Nearly 50 African heads of state and government will gather next week for an unprecedented meeting in Washington that has high hopes of reframing the continent’s image, from one defined by conflict and disease to one of a region ripe with economic promise.

The U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit — which marks the first time an American president will have convened Africa’s leaders in a single conference — faces major hurdles ranging from the ongoing distraction of other foreign conflicts to domestic budget constraints. Obama administration officials have deliberately downplayed expectations, saying the event will not conclude with the sort of flashy financial commitments that Chinese leaders have unveiled at African summits held in Beijing.

Instead, the meeting will focus largely on the economic potential that Africa offers America — provided that the two regions can collaborate to solve ongoing problems around electricity supply, agriculture, security threats and democratic governance. It could allow President Obama to establish a broader legacy in Africa: his deputy national security adviser, Ben Rhodes, told reporters Thursday that the meeting “can be a game-changer in the U.S.-Africa relationship.”

On Friday, President Obama said that “the importance of this for America needs to be understood. Africa is one of the fastest-growing continents in the world. … You have all sorts of other countries, like China and Brazil and India, deeply interested in working with Africa.”

Sen. Christopher A. Coons (D-Del.), who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee on African affairs, noted that the United States still has strong ties based on years of development assistance. “I think history will show Africa is the continent of the greatest opportunity this century,” Coons said. “We have a moment that is passing us by, and we should build on these relationships.”

Linda Thomas-Greenfield, assistant secretary of state for African affairs, described the summit as “cementing what is already a strong relationship between the U.S. and Africa, as equals. . . . We’re being very clear and open, this is not a donor conference.”

The event is, in fact, a sprawling networking affair that will bring together foreign dignitaries, American and African CEOs, policymakers and activists for several days of business deals and panel discussions, as well as private dinners and at least one dance party. There are close to 100 side events, on top of a three-day formal conference that includes one day solely devoted to business issues and another to discussions among country leaders on peace and security, as well as health and other development issues.

State Department officials have been scrambling to prepare for the massive event. The department’s first-floor bathrooms are being renovated in anticipation of the conference, while a breakdown in its computer system has delayed the issuance of visas for some delegations.

Other preparations, however, are set. Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker, who will lead the business segment along with former New York mayor Michael R. Bloomberg (I), is slated to announce new deals between the United States and Africa totaling $1 billion. Rep. Gregory Meeks (D-N.Y.), who is co-chairing a reception in the Capitol on Monday night, said his goal is “to have some real deals that are cut” before the guests polish off their appetizers and drinks at his event.

The less-formal nature of the conference — especially compared with ones in countries such as Japan, where the prime minister personally sits down with each visiting head of state — has raised concerns in some quarters. Some African leaders were surprised when they first learned they would not deliver individual speeches, and Obama has opted for large group discussions rather than one-on-one meetings.

House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Edward R. Royce (R-Calif.) said in an interview that while he recognizes the problem of favoring some politicians over others, the administration also risks offending “some of our allied partners” by not providing private audiences with the president.

Still, Witney Schneidman, who was deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs in the Clinton administration, said the Obama administration’s “creative” approach makes more sense.

“If each delegation got 15 minutes, that would be twelve and a half hours,” said Schneidman, a senior international adviser for Africa at the Covington & Burling law firm and a Brookings Institution nonresident fellow. “Is that how people really want to spend their time?”

Jennifer G. Cooke, who directs the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Africa program, said the larger question facing the administration is that in the absence of major new policy announcements, to what extent can the summit deliver concrete results.

“There will certainly be some leaders who walk away and say, ‘What was that all about?’” she said.

Obama’s two predecessors had a single policy achievement that defined their approach to the region. In the case of Bill Clinton, it was the African Growth and Prosperity Act (AGOA), which reduced some trade barriers between the two partners. For George W. Bush, it was the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The administration has continued those two programs while launching initiatives to promote food security, electrification, training for young leaders and regional trade between African nations themselves.

As the child of a Kenyan father, Obama faced high expectations from Africans and specialists in the region when he took office. Both the president’s friends and foes say he disappointed many Africans in his first term, when he focused largely on the struggling U.S. economy and passage of a sweeping health-care law.

“Today the consensus among those same people is that he missed the mark,” Royce said, adding that Obama has not moved swiftly enough to address instability in places such as Sudan or terrorist threats such as Boko Haram. “The president’s approach to Africa has been more reactive than proactive.”

But even Royce said Obama had elevated the issue in his second term, and administration officials and several outside experts said the president and his top deputies were focused on fostering closer ties with Africa at a time when many other countries — including China — are increasingly focused on the continent. The United States still invests more in Africa than any other country, but trade between China and Africa has now surpassed that between America and the continent. The European Union, Brazil and others are eyeing a region that boasted six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies in the last decade.

“Africa also has strong ties with other regions and nations, but America’s engagement with Africa is fundamentally different,” said national security adviser Susan E. Rice in remarks at the U.S. Institute for Peace on Wednesday. “We don’t see Africa as a pipeline to extract vital resources, nor as a funnel for charity. The continent is a dynamic region of boundless possibility.”

Business leaders are intensely focused on the summit. The chief executives of Coca-Cola, General Electric and other major firms will be in town, while the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is hosting 11 heads of state in seven separate events. One is a banquet dinner at the Grand Hyatt Hotel honoring Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan; another is a much smaller dinner at the Chamber’s headquarters with the Ivory Coast’s president, Alassane Ouattara, featuring a feta and watermelon salad as well as grilled chicken breast with smoked sweet peppers and a caramel-roasted lemon sauce.

Scott Eisner, the Chamber’s vice president of African affairs, said he and others had been pressing the administration to host such a summit for years, because, “If you want to get CEOs to pay attention, you need to have your commander in chief leading the charge.”

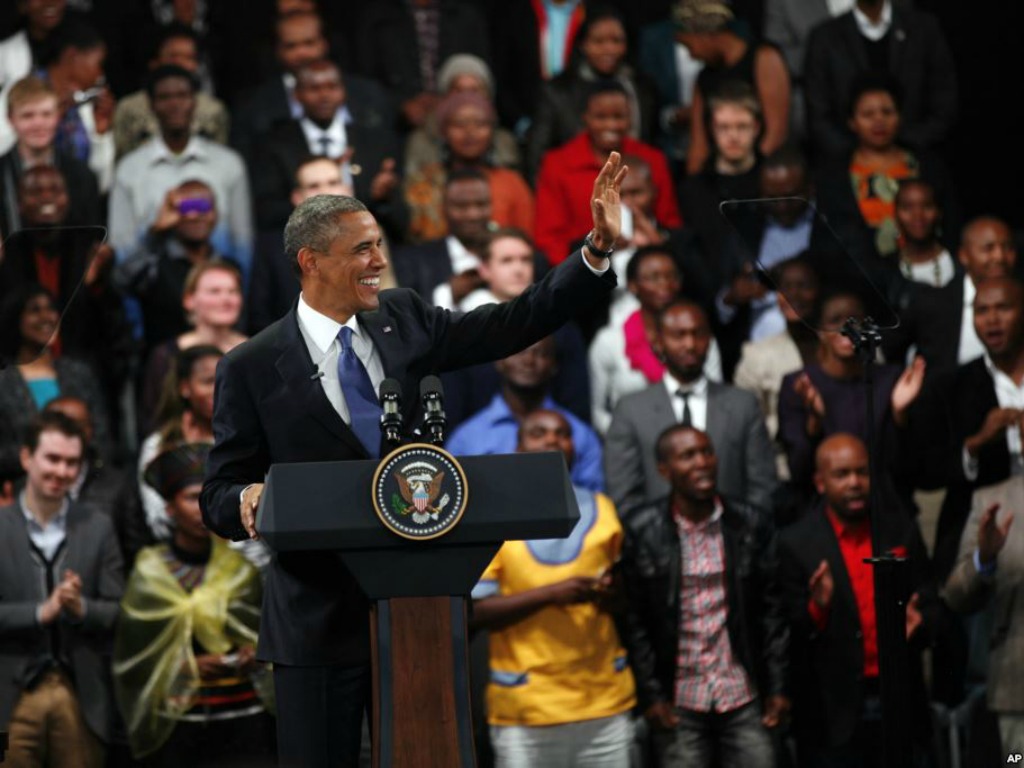

Human rights groups have questioned why the administration is not integrating members of civil society more fully into the sessions involving Africa leaders, given that roughly a dozen African nations have moved in recent years to crack down on dissent and minority groups, including lesbians and gays. Separate sessions on civil society will take place on Monday, while 500 young African leaders met with the president this week.

Sarah Margon, Human Rights Watch’s Washington director, said the fact that African activists will not have a chance to speak directly when the leaders are gathered together “really contradicts the administration’s rhetorical commitment to civil society, independent voices, and independent media throughout the continent.”

Thomas-Greenfield said organizers decided to keep the activists on a separate program because “the actual summit is a summit between leaders,” but added, “We want to have frank discussions with those leaders on the issues that civil society brings to the table.”

Only a handful of heads of state — from the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Sudan and Zimbabwe — were not invited to the summit, and Margon noted that leaders such as Equatorial Guinea President Teodoro Obiang would be feted by corporate groups even though his administration has faced serious corruption and human rights charges during his nearly 35 years in power.

“Then they’ve made the circuit, they’ve made new friends, and they don’t have to answer any questions about their blemished records,” she said.

A separate reason — the outbreak of the Ebola virus — is keeping the presidents of Liberia and Sierra Leone at home.

And even as there is growing corporate interest in Africa, the continent still faces huge economic challenges. More than 70 percent of Africans do not have reliable access to electricity: Obama has pledged $7 billion in federal assistance and loan guarantees through his Power Africa program and the private sector has matched this with another $14 billion, but a House-passed bill to make the program permanent has yet to make it through the Senate.

Amadou Sy, a senior fellow at Brookings’ Africa Growth Initiative, noted that the gross domestic product for all of Kenya is smaller than the size of the economy in Madison, Wis., while the amount of electricity used on game night at the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium is equal to that consumed country-wide in Liberia.

Still, there are signs of a change even when it comes to the push for development. Three decades ago, Western pop stars recorded “We Are the World” to raise money in response to the Ethiopian famine; recently the ONE campaign helped gather 2.2 million signatures from Africans urging more investment in agriculture, in part through the song “Cocoa na Chocolate,” which featured only African musicians.

Sipho Moyo, ONE’s Africa director, said this shift “does mean that Africans, and African leaders, become more responsible for the health challenges, the education challenges and the development challenges.”

Perhaps Obama, she added, “will be remembered as the president who changed the narrative about how we view Africa.”